A Real Bug’s Life

Shrinking the Camera Crew

A Conversation with Robert Hollingworth & Henry Keep

By David Daut

In 1998, Pixar’s sophomore feature film A Bug’s Life showed audiences an “epic of miniature proportions,” cleverly blending the fable of The Ant and the Grasshopper with the structure of Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai. Now, more than 25 years later, National Geographic’s A Real Bug’s Life similarly aims to give audiences a “bug’s-eye view” of the world, this time by showcasing real insects—as well as arachnids and other assorted arthropods—in their natural habitats.

To learn about the unique challenges and groundbreaking technology used to shoot this documentary series, Camera Operator spoke with photographer Robert Hollingworth and focus puller Henry Keep. Whether it was working closely with entomologists to ensure that not even one cockroach was misplaced or creating camera lenses barely bigger than a hypodermic needle, the work that went into capturing these tiny subjects was anything but small.

From the bustling streets of New York City to the pastoral beauty of a country farm, bugs are everywhere. In cracks and crevices, in hay bales and on flowers, and even, occasionally, on your food. Despite their creepy, crawly reputation, bugs are an essential part of our ecosystem, and National Geographic’s new documentary series aims to give viewers a better appreciation for these creatures by letting us see the world through their eyes. A Real Bug’s Life is produced by National Geographic and is narrated by Awkwafina.

Camera Operator: Because Camera Operator typically tends to cover more scripted narrative programs, I want to start with a high-level look at what it’s like to shoot for a nature documentary. How much of your time, for instance, is spent trying to capture specific animal behavior versus being on the lookout for interesting, spontaneous moments? What other differences can you think of between something like this versus a narrative feature film or television show?

Robert Hollingworth: The big difference is that it’s a natural history show versus a scripted show. You’re trying to weave a story out of natural behavior, a natural narrative. With scripted, we would start with a storyboard and a script; you’re in more control. With this, we very much rely on experts in their field, animal behavior experts or entomologists. We work with them very closely, and they collaborate with directors and producers, together weaving a story from that. I suppose it probably starts with a wish list, in that you would try and find a really interesting story, and then you work out how to visually capture that story in the most engaging way possible. So, early days, long before I’d ever be anywhere near the project, you’ve got producers and directors speaking to, in this particular case, entomologists.

CO: So, you have an idea, or a rough framework of the kind of stuff you want to get, but then it’s about finding the specific moments within that kind of broader framework. Is that right?

Hollingworth: You want to tell a story, much like you would with narrative, but it needs to be real. That’s the thing. It’s a real story, it’s A Real Bug’s Life. So, it’s finding an in there and being practical about it. Filming this stuff is really hard—it’s really, really small. With an actor, you can place them on a mark, but with an insect, you’re just hoping that they’re going to do what you want them to do. You’re trying to load everything in your favor to capture it because, as you know, the nuts and bolts of filming is that you’ve got a finite amount of time and resources available. You have the same problems that you have in narrative, but there’s that added layer of not being able to “speak bug.” You get a translator such as [entomologists] Tim Cockerill or Graham [Smith] and Janice [Smith] and many others that we worked with as well, and they help you bridge that gap between your subject and you.

CO: And like you mentioned, the difference in scale is the most noticeable thing about this project, where the subjects are incredibly tiny and often hidden away inside of small cracks or tight crevices. Could you talk a little bit about how you went about shooting for the series? I know there were some new technologies that aided in your work.

Hollingworth: We were a huge team. I’m just one person representing a highly skilled camera team and wider crew beyond that, often with specialties in different parts of filmmaking that come together. The challenge with this is you’ve got to shrink your film crew down to the size of your subject. Nat Sharman, our series director, was constantly saying that to us. It’s quite an exciting challenge imagining we are all shrunk down to the size of an ant. What would an ant-size film crew do? That’s a really good way of looking at the challenge and looking at the relationship you have with your subject. Your aim is to make it as cinematic as possible, as dramatic as possible. We’re using the likes of Raptors and ALEXAs and Venices. So, then it’s a case of how do you reduce that down to something the size of a bug?

We used a variety of different lenses. Some of them more readily available, like Laowa probes—which are excellent—and others that we’ve had specially built. There’s a lens series that make the Laowa probe look massive. They’re a little bit bigger than a hypodermic needle and were made by one of our camera operators on the series, Chris Watts. He built these lenses, and they’re quite extraordinary. The entrance pupil is tiny, even smaller than a Laowa probe. If you were to sit them next to a spider, they would be much smaller than the spider. So, they’re immediately shrinking your perspective down to that of your subject. And that’s probably one of the big challenges that we overcame for this series was this idea of getting your natural history film crew and shrinking it down to the size of the subject. How do we do that in reality? And reality is these sorts of innovative lenses. But, it’s a combination of everything. We also use conventional lenses for wides and establishers, and it’s the usual visual language to get those bigger shots.

There are other things as well, like absolutely tiny racing drones. Racing drones that have been made even smaller and even more zippy—we have people building those and flying those for us. We also built a motion control system so that we can operate the camera with the same fluidity that you would operate a fluid head on a human scale, but we had to take all that grip equipment and shrink it down, again, to bug-size. That was a pioneering motion control four-axis system so the camera can move anywhere within an 18-square-inch area. There is pan, tilt, and two linear axes—X and Y—and then there’s also a Z axis if we want to go up and down. It is operated with a PlayStation 4 controller, so the operator can operate the camera intuitively. I’d be on the monitor, and I was able to fly with the camera with the PS4 controller—I didn’t have to look at it or worry about the grip, it could just be somewhere else.

Then Henry is like the fifth axis: he’s focus. A good example of this is the pavement ant scene in New York. Pavement ants are absolutely tiny—only a millimeter or two—and to shoot the scene, we were shooting on this motion-control system on a RED with a selection of macro lenses and probe lenses. I was able to just concentrate on the monitor, I didn’t need to look at the set or anything at all. I could be flying the camera, and Henry would be on another monitor, making sure that it was always in focus. Is that right, Henry?

Henry Keep: Yeah, the bits of kit that Rob R&D-ed and made for this work have been fantastic. You just wouldn’t get to that level of cinematography and cinematic movement and quality without it. Being able to hunt and find unique shots and perspectives, little subtle tracking shots and push-in, push-outs with millimeter accuracy was fantastic. I’ve done a lot of observational focus pulling on shorts and on features, but there’s a different level to doing it where your focus pull is half a millimeter in depth. We’ve worked together solidly for about two-and-a-half years. On big features, large teams are expected. But on natural history, teams are a lot smaller and often multi-disciplinary. For Bug’s we had a larger team at times including [Jib operator] Dave Brice. When we’re on Rob’s macro gantry, it’s him and myself, and it feels like you’re on a large set with what you can create, but we’re doing it on the macro level. It’s wonderful. It’s so satisfying when you nail a shot. You have to have a lot of patience. You can predict what their behavior will be with the pheromone trail that our bug specialist has helped lay for ants to go a certain way, but they still like to do their own thing, so you have to react very quickly. Hopefully by looking at the shots that we captured you can see the difference. Different types of motion we’ve managed to capture. It’s great fun to do all of those sequences. Pavement ants was a great one to do.

CO: Henry, digging into what you said a little bit more—focus changes that are less than a millimeter in distance. How much do you have to retrain the way you think and the muscle memory of doing those adjustments, or does it come fairly naturally with the way the technology is?

Keep: With the lenses that we had made and used, there was a little bit of retraining my brain, especially using diopters and extension tubes. They will alter the natural characteristics, so you have to be really aware. If we are going for the ultra-tight focus on the eye of an ant, we’ll put an extension tube on it and you know that we have to be within four to six inches in front of the lens, that’s our tolerance. So, we’re just allowing for those sort of things, but it’s surprising how, after just a couple of shoots—just getting my head around a few of the bits of kit—it’s the same principles as all other focus pulling. I feel like you had to be a bit more reactive and really chat with the insect wranglers to understand the behavior, knowing change in directions, because bugs can go fast. And then while we’re on set, it’s just learning by doing and seeing.

If the particular shot we’re trying to get is really tough, there is the patience element. There was an aphid sequence where we were on a high-speed Phantom camera for getting the honeydew secretion out the back end. That shot, we’d lined up for it because that was a fixed one; that was with the pre-record of 1.8 seconds on the Phantom. We’d set everything up, and it was just a case of triggering the motion. I was there for an hour-and-a-half, blink and you missed it, and glued to the screen, just to get that one shot. So, compared to features, the patience element is huge.

Hollingworth: The other comparison to features, Henry, is you spent your lunch break also doing that, I remember.

Keep: Yeah, I had that on the side. I just tried taking a bite while waiting.

Hollingworth: You couldn’t have a break because it could have happened at any moment. Also, to your credit, you were pulling focus at a thousand frames a second. Many times during the series, you were doing focus pulls on the Phantom.

Keep: Yeah, we definitely had to have patience for that. Any other focus pullers that do high-speed know that you can have all the preparation in the world, but just half-a-second out equals 20 seconds out in real time. There was the sequence of a bat versus moth, and that was predicting the flight path of a bat coming and doing a near miss on a moth. That was tricky, but hugely satisfying when you nail a shot, I think even more so than drama. I feel sometimes you can be quite clinical in drama because everything’s mapped out. You’ve seen the rehearsal, you know where things are going to be, and it’s just slight adjustments during takes. Whereas with this, there’s so much randomness. When you actually nail a tricky shot, it’s hugely satisfying professionally to work on that sort of sequence.

CO: You’ve both touched on this a little bit, but I wonder if you could speak a little more to working with the bug wranglers and the entomologists to understand the behavior of these animals. What was that like?

Hollingworth: It’s essential—we wouldn’t be able to do it without them. I know for some people, the idea that we’ve got a bug wrangler demystifies it a little bit, but it’s an essential part of the process. They’re very much like a translator, giving you the conduit into your subject. For example, there was one particular moment I remember working with Tim—one of the several bug wranglers we worked with who were all absolutely excellent—we were lining up to do a takeoff and landing of a butterfly. Takeoff’s fine because if you wait long enough, eventually it will fly, but landing is very hard. We were lining up on the takeoffs, and Tim just suddenly said, “a couple of inches to your left and down, landing.” So, I just quickly flicked the camera over, and then a butterfly landed right into the middle of the frame. It’s moments like that that make a film. They can be magical moments, but they come about through not making an animal do anything at all. It landed entirely of its own volition, but it was the fact that Tim in this instance was monitoring the behavior, staring at it for ages and was able to predict it. That’s where the relationship that we have on set with the animal handlers makes or breaks the scene.

Keep: Yeah, agreed. It elevates your hit ratio hugely. I’ve been chatting to people in [the BBC’s Natural History Unit], and it was sometimes the directors, the producers, or the camera operators that would do wrangling on older shows, and you detract from the quality of shots as a result. You’re trying to do too many things. Having that extra specialist crew to be able to get the behavior means we can focus on capturing the shot and nailing the shot. Marrying those all up means your hit ratio is so much higher than a decade ago, and sequences back then would take maybe twice as long or longer to capture the same shot.

Hollingworth: Yeah, we’re more efficient. It’s interesting to talk about this in comparison to narrative. I think there’s a convergence now of narrative and natural history in terms of the disciplines involved. Henry being a focus puller on our series, that wouldn’t have happened three or four years ago. The operator would be doing their own focus on the lens. And then there were shoots where we’ve had gaffers in, shoots where we’ve had a grip in, like David Brice. So, the worlds are converging, I think.

CO: You’ve both touched on a few shots that were particularly satisfying to get. The pavement ants, the butterfly landing. Are there any other specific moments that spring to mind of shots that were uniquely challenging or satisfying?

Hollingworth: I suppose one of the really satisfying scenes was on the New York episode with [Director of Photography] Simon De Glanville. That episode was done principally by Simon, and then I was kind of his second unit, which I’m very proud to be, because Simon’s excellent. Simon shot the location stuff in New York and the cut-ins we shot on a studio set that we built. That was very satisfying because to be able to do a built-environment set was a lot of fun. The lighting could be full of practical lighting effects. Our actors here were cockroaches, and they have a reflective body, so to be able to have lights pinging off parts of their body in macro detail as they walk along or as a taxi whizzes past added a sense of immersion and environmental reality that really elevated the scene.

That’s the other thing about A Real Bug’s Life. It’s real bugs, but it’s real bugs done in a real way as well. We were trying wherever possible to use practical lighting effects if we were doing built-environment work, and for me, that idea just completely elevates it. Working with insects is all about details. They’re tiny, so everything is detail oriented, and I found that very satisfying. On the cockroach scene, we did a two- or three-day repeat move on a set that was meant to be underneath the sidewalk. There were dripping pipes and it was just a dank, grotty area. It was meant to be something that humans will look at and go, “that’s disgusting,” but something our heroes look at and go, “this is heaven!” The reality is that it was a two- or three-day shot, where the camera is doing a repeat move on motion control.

Keep: That was the “Welcome to the Bugway” in Akwafina’s narration. A cockroach comes out of a pipe and it pulls back to reveal this underground sewer sort of scene. That was very challenging. Once we’ve mapped out the shot, you had to get the various different insects to go within this area and individually be comped out so that you could add one cockroach to do a pass, and then a millipede to do the next pass. I can’t remember the exact number, but it was something like 40 separate insect passes that were all composited into one. VFX came in and did a LIDAR scan of the set so they could map it all, but every insect in that is all real, and we had to allow for multiple times for each insect so that we see where they were going and they wouldn’t overlap on the shots. It was a big, big setup, but actually as a lead-in for that scene to the underground world of insects, it worked really well.

CO: And it’s a great shot in the show. You sort of know watching the series that there’s a little bit of CGI sweetening that goes on—and it says as much in the credits of each episode—but like you said, it’s all still the real behavior of the insects, even if you’re compositing things on top of each other. But it’s interesting to hear how you pulled that scene off.

Hollingworth: Yeah, that was done with the Laowa probe. For me, I think it’s a really important relationship you have with your entrance pupil to your animal. So, cockroach versus Laowa probe of about 18 millimeters, they’re roughly similar, so you’re immediately in the world of the cockroach. You’re on their level on their scale. That sets the relationship up, and then we built a macro Technocrane so the camera could do a complete pullback and not see any of the grip that it was being held by. We had three linear macro rails mounted on top of each other so they would telescope forward and backwards, and there’s a focus pull keyframed in on top of that.

But to the point about not wanting to trick the audience—and speaking entirely personally—you could think, “It’s A Real Bug’s Life, so why are you VFX-ing things and compositing?” The reason that we would do it in that scenario is that we could have done the shot once, and we could have tipped 500 or 1,000 cockroaches in there, but then we would have probably created an infestation in the studio. They could have escaped, they would reproduce, and to the local environment that is a problem. You couldn’t do that in New York on the street, so you have to do it in a controlled environment studio, but you still have to be careful that you don’t create an unwanted infestation for the local community.

CO: Yeah, of course.

Hollingworth: So, it’s one of those things where doing a composite shot is actually the safer thing to do. And it’s also the safe thing for the animals. If you have lots of cockroaches, some of them might come to harm, they might get lost. Our entomologists are unbelievably strict about a one-in, one-out policy, even for a cockroach. If four get released onto the set, four will get recovered, and we don’t carry on filming until all four have been accounted for. We haven’t lost a cockroach. Is that fair to say, Henry?

Keep: Yeah, definitely right. When we’re doing the slightly wider shots where there were four or five on the set, because I was on the focus wheel next to the monitor, I also had a pad of paper on the side, so I’d do a tally in and out. And then entomologists are watching, because that’s where we had Tim and Lucia for the larger setup so they could have eyes on where they are. Once we nail the shots, we tick them in, tick them out and be very, very careful in order to not lose any.

Hollingworth: By layering up the shot, you can work with a couple of individuals and you know that they are accounted for and you’re not creating any problems for the local community of wildlife, or indeed hurting any cockroaches. From my point of view, I think that’s the right thing to do. It feels like the right thing to do from an animal welfare point of view, but also a storytelling point of view, because what we’ve ultimately created without using any CGI is real, as in that would actually exist. We haven’t created a scene that wouldn’t exist. We’ve just been creative in the way we capture it.

I should also say, lighting has really leapt on in the last five years. It’s principally LED—no shock there—but it’s really got to the point now where the quality of the light is excellent. And it’s cold, which means the animal behavior you’re getting is much more real. If you’re heating an animal with an HMI, then there’s not just visible light there, you’ve got UV and IR going in and the response from the animal is noticeable. A lot of the delicate touches in A Real Bug’s Life on the palate comes from the fact that we can get higher ISOs on cameras—fantastic—combined with lower light levels, both because of the high ISO and also because it’s LED. So, you can get more lighting without adding the heat and without adding ultraviolet. UV in particular upsets them a lot. So, you’re getting more natural behavior.

The moth and the butterfly flying against the moon, which is one of the stills that Disney released, it was just absolutely enchanting to shoot that. But that was because of LEDs that we could do that, because we were shooting on a Phantom. Normally Phantom equals big, bright lights, which are blunt tools at the best of times, whereas with that moon shot, the whole thing was shot on LEDs. It was ETC Source Fours.

I’ve already talked about shrinking down the entrance pupil of your lens, but the other thing we shrunk down is the size of the lights. There’s a company in UK that made me some fiber optic lights, and there’s a selection of tails on the end of them from16 millimeters down to 1.5 mm. You can also lens them with Fresnels or PC lenses. Broadly speaking, you’ve got an LED light source that’s flicker-free at 1,000 frames a second that can be the same size or smaller than your subject. So, instead of lighting your ant or cockroach or something with a 10-inch Fresnel or something massive, you can light it with something that’s two or three millimeters across. And that allows for a lot more dexterity and more nuanced lighting instead of just turning a light on and blasting it. If you light a small thing with a very large light, your shadows don’t make any sense, whereas when you start shrinking your light sources down, suddenly, everything makes sense, because the lens is a relatable size to the animal and the light source lighting the subject is also relatable.

So, those are the techniques we employed. Really satisfying when you can light a grungy area nicely, you can come up with quite a fun little motion-control Technocrane, which you had to problem-solve and think up and create. Chris Timmins was on that as well. Another insect wrangler. I think that was probably one of my highlights.

Keep: Chris Timmins, the Mr. Miyagi of bumblebee wrangling. When you’re working with bumblebees in a controlled environment, doing all these interiors, doing smaller things, you’re able to recover your bumblebee for each shot and reset. Outside, though, if they fly away, that’s it. So, Chris Timmins was amazing. We wanted a shot following a take off, and once the bumblebee would fly, we’d expect, “Oh, he’s gonna have to find another one.” But he just plucked it out of the air. He just cupped his hand around the bee mid-flight and then said, “Reset, ready to go.”

Hollingworth: The first time he did that, I thought it was a joke, as in the bumblebee took off. And he just went, “No, it’s here. It’s ready to go again.”

Keep: Yeah, that’s really when you know you’re working with an insect specialist.

CO: That’s incredible. You talked about doing the set work on the New York episode, but tell me a little bit more what it was like shooting on location for the farm episode.

Hollingworth: We were on a farm in Buckinghamshire in the UK. Each episode has a home, and the farm was our home for that episode. We started on the farm in a slightly more narrative-driven way insofar as we kicked off doing some big wide shots as we immersed ourselves in our environment. In a more documentary way, we spent some time there to work out what parts of the farm we liked and where our little stages could be set. We found the little areas that we liked including tractors, barns, horses, and even a combine harvester.

And that’s where Dave Brice came in, because we had quite a lot of grip there; quite big grip, because we needed to get the camera up and over the tops of the barns for various moments where spiderlings are flying through and then landing, or bee journey, or simply establishers. Like I said, we kicked off the farm with a more conventional way of filming. We’re on a Venice for its full-frame nature—we wanted to really soak in the environment. So, that was a deliberate choice there and that’s the camera that was on the crane most of the time. What head did we have?

Keep: Ronin 2, we were on the crane with, so that enabled us to get those jib shots. Also with the horsefly sequence we were doing the wider shots, we’re also on the Ronin for that so we could switch between crane and when you were going round with the EasyRig on. That worked out very well to be nice and fast because you’re still working with animals and insects, so we didn’t have the time to be too slow in changing between the setups. It’s a bit more of a documentary-esque nimbleness to the crew and selecting what kit we used. We did some slider elements on that as well, didn’t we?

Hollingworth: We had a 1.2-meter/four-foot slider. We did quite a lot of establishing shots on the farm where we tried to set our world. And then we came back because we were there for a year, on and off, to capture all the seasons. There were some very lovely happy accidents along the way. The chickens were one of them, for example. We didn’t expect to necessarily feature chickens, I don’t think the director Alex was necessarily going for chickens, but there were chickens on the farm, we filmed the chickens in dawn light one day, they looked beautiful on the Mamiya lenses; a lot of the wides were shot on Mamiyas. The chickens were just fun. They had tons of character, and we just decided we could do something where it seems like the chickens are going to be a threat to the bee. In actuality, the chicken is not a threat to the bee—the two live together very harmoniously—but you could pose it in that way.

Nathan Small, who was filming as well, went back and then shot some really nice details of the bee in floorboards. It’s one of those things where you get the idea and go, “Actually, that’s quite nice, let’s make more of it.” We’d move on to a different series while Nathan was shooting those sorts of moments for us and layering it up. It’s really nice, actually. It had a very different feel by virtue of the fact that, because it was local to us, we could keep nipping back. There’s a spontaneous element there that you didn’t have available on other locations. For instance, Nat was filming in Africa; you can’t just spontaneously hop back to Kenya as easily as you can down the road to the farm.

And the other thing we did there was we doubled a studio. My studio, where we shot quite a lot of scenes, is in the middle of some fields and there’s a lovely summer meadow nearby. We filmed the summer meadow scenes in that field, and there was a slightly documentary approach to that. We had a slider and crane so that we could still move the camera with some degree of deliberation, but also be able to relocate it around the field. Graham and Janice were our wranglers for that. From an animal welfare point of view all the wildlife were already in the meadow. If we wanted to film a butterfly, for instance, Graham and Janice would be able to either go and pick it up in a net and put it on the flower we’re lined up on, or they could put some sugar water down to entice them over to where we are. It’s those sorts of methods we used to actually work in the wild.

If you are shooting macro a lot of the time, it’s very claustrophobic, particularly if you’re on a long focal length. Your background just gets lost. So, these probe lenses that we used a lot, or as Henry said, the wide lenses with diopters and extension tubes enabled us to give you a wider field of view and therefore soak in that world. It immediately feels richer and there’s more volume. But shooting in the meadow ultimately was a side effect of efficiency in filming. We had a set number of weeks to do some filming, so we could film in the studio if the weather was bad, knowing that if the weather was suddenly great for the afternoon, we could pile everything into the van and drive 10 minutes down the road to the meadow and keep shooting. We’re able to be responsive and opportunistic on good weather days because we wanted to shoot during golden light. We were dynamically scheduling our stuff, which I suppose is something you try and do in narrative, but you often can’t.

Camera Operator Spring 2024

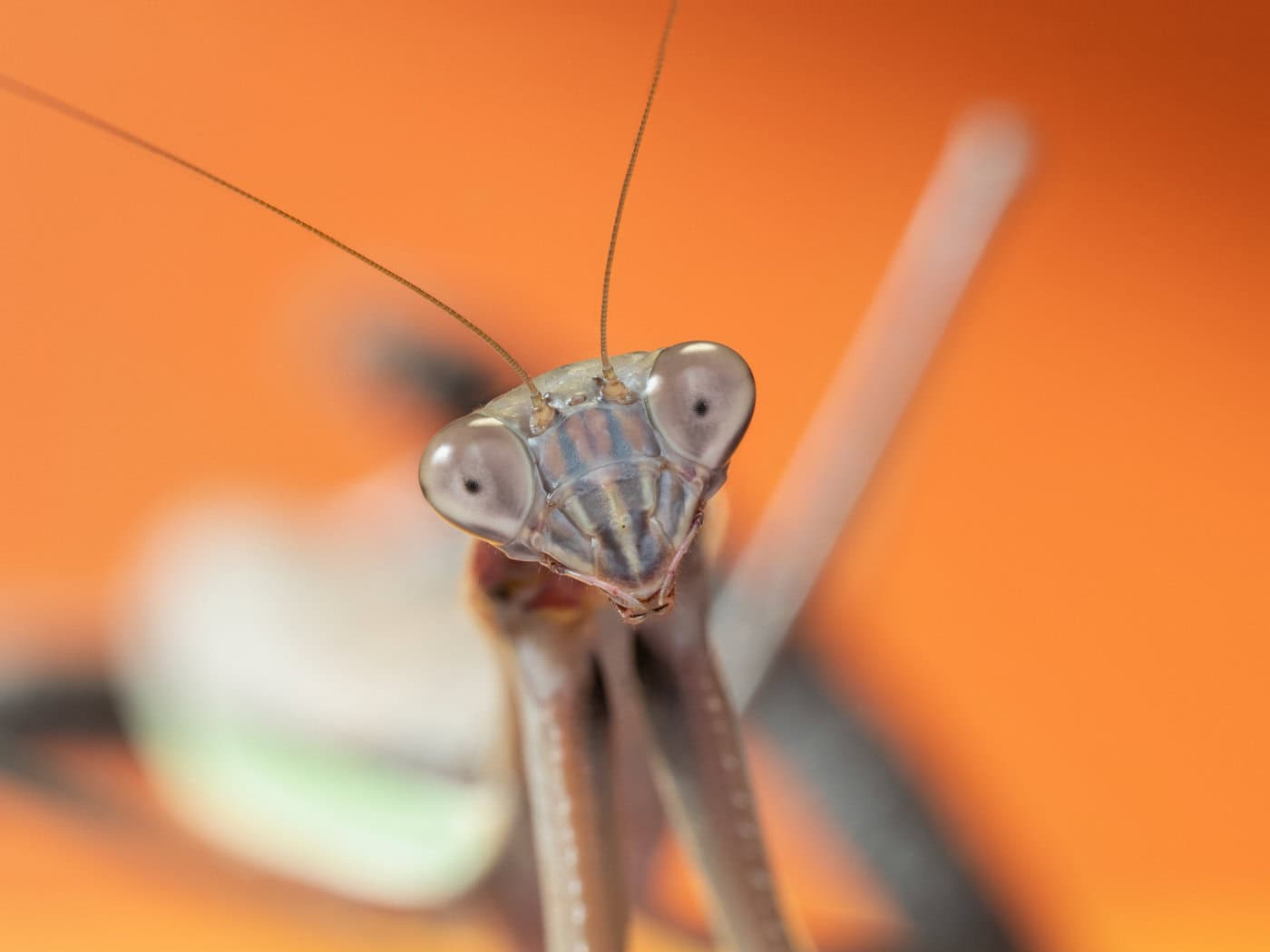

Above Photo: Animal wrangler Tim Cockerill handles a praying mantis during a shoot for “The Big City” episode of A REAL BUG’S LIFE.

Photos by Tom Oldridge, Nathan Small & Euan Smith for National Geographic

TECH ON SET

RED Gemini

Sony Venice

Phantom VEO 4K

Mamiya M645

Primes & Macro Primes

Nikon AIS Primes & Nikon Macro Lenses

Macro Gantry–Motion Control

Ronin R2

GF8 Crane & Dolly Track

Atlas Slider 1.2m

RT Motion Follow Focus

RELATED CONTENT

Watch the Trailer for A Real Bug’s Life

Robert Hollingworth

Learn more about Robert’s career and projects at IMDB.com

Henry Keep

BEHIND THE SCENES

Select Photo for Slideshow

Robert Hollingworth

Robert Hollingworth is a director of photography with over 12 years professional experience in photography and filmmaking under his belt, working for some of the world’s most respected media outlets and producers. As a keen communicator of the natural sciences and visual storyteller, Hollingworth has built up an impressive body of professional experience in natural history filmmaking. He has played a pivotal role in the production of several major documentaries, including Hidden Kingdoms (BBC1), Micro Monsters (Sky), and Mysteries of the Unseen World (National Geographic). He has maintained a strong interest in the technical aspects of filmmaking, taking pride in his ability to design and engineer equipment to fit the often difficult specifications of a particular shoot. Engineering creative solutions during the course of film production, including pioneering new filming techniques, earned him a nomination for a BAFTA award in the category of Special and Visual Effects for his work on the landmark documentary Micro Monsters.

Hollingworth’s passion for biological sciences is only equaled by his love for communication through visual storytelling. This belief that science should be enjoyed by all continues to inspire both his work and his mission to narrate the world.

A writer and critic for more than a decade, David Daut specializes in analysis of genre cinema and immersive media. In addition to his work for Camera Operator and other publications, David is also the co-creator of Hollow Medium, a “recovered audio” ghost story podcast. David studied at the USC School of Cinematic Arts and works as a freelance writer based out of Long Beach, California.