West Side Story: Musical on a Massive Scale

An interview with Mitch Dubin, SOC, and John “Buzz” Moyer, SOC

By David Daut

In this dynamic retelling of the seminal musical West Side Story, Steven Spielberg takes us to the Upper West Side of Manhattan in the mid-20th century as young lovers Tony and María forge a romance amid a hotbed of racial and economic tension. The film stars Ansel Elgort, Ariana DeBose, David Alvarez, Mike Faist, Rita Moreno, and Rachel Zegler, with a script by Tony Kushner.

Principal photography on Steven Spielberg’s new adaptation of West Side Story wrapped in September of 2019. More than two years later, it finally arrived in theaters to rave reviews, praising the cast, the direction, and—in particular—the camera work. It’s a film that preserves the beating heart of the original story while at the same time pushing its style toward something much more bold and cinematic.

Camera Operator magazine got together with A camera operator Mitch Dubin, SOC, and Steadicam operator Buzz Moyer, SOC, to talk about what went into taking on a big, classical musical like West Side Story, something Steven Spielberg has said he’s wanted to do for the better part of two decades.

In this conversation, we talked about what went into making the film’s striking opening shot, the specific challenges of shooting elaborate dance sequences, and trying to work while fighting back tears during some of the film’s most emotionally intense scenes.

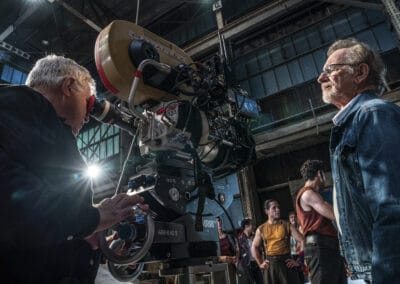

John “Buzz” Moyer on the set of WEST SIDE STORY

Camera Operator: Jumping right in, Spielberg is well known for his so-called “invisible oners,” but West Side Story starts with the not-so-invisible oner in its opening establishing shot. Could you talk a little bit about what it took to pull that off?

Mitch Dubin: I’m gonna preface this interview with—and I’m sure Buzz will agree—the fact that we shot this movie two-and-a-half years ago. It was the summer of 2019. That in combination with the fact that I know personally, for me as a camera operator, we get sometimes so focused on the frame and what we’re doing that you get completely absorbed and tune everything else out. Once we finish the shot, check the gate, and walk away, I forget everything. Even if we had shot this film last week, I still wouldn’t remember a lot of things because it’s the nature of a camera operator’s mind; you have to concentrate so diligently on the specific frames that you don’t remember anything. I would go to dailies—in the days we used to have dailies—and I’d say, “I don’t remember shooting this.” Or you go to see the movie in the theater and you say, “God, did I shoot this film?” I don’t know, Buzz, if you agree with that.

John “Buzz” Moyer: Yeah, for sure. Certainly watching this movie last night, I was so absorbed with what was going on. I felt so distant from being involved with it in the first place and was sucked into the show before I realized, “Oh my gosh, I think I did that one.” But yeah, I definitely agree with what Mitch said.

Dubin: I’ve seen the movie twice now. The first time I saw it I was taken aback by the energy of it and the in-your-face camera work. It was startling. It was a sensory barrage, which is fantastic! When I saw the movie the second time, I saw it on a bigger screen with a bigger audience and that’s when I actually saw the film. I don’t normally get emotional in movies (especially ones that I have worked on) but when I saw West Side Story the second time, I became emotionally involved with the story and the characters.

But going back to your original question, that shot was very complicated. Steven doesn’t normally storyboard or previz, but he does on certain complicated shots, conceptual shots, visual-effects shots. That sequence was storyboarded, but even following those storyboards was complicated because the way things are drawn is not the way things are in reality. It started on a telescoping crane, then it transitioned into a drone shot that then transitioned back into a crane shot. So it went crane, drone, crane, plus all the added visual effects. Those big demolition balls were VFX created, but still, you had to know where to put the camera to make sense where they put in those wrecking balls. All the half-demolished buildings were a constructed set in Paterson, New Jersey. We had to match up the “A” part of the shot to the “B” side of the next shot. We used the windows of the building as guidelines to where they would appear in each shot. It was complicated.

CO: Going back to what you were saying about shooting this so long ago, pre-pandemic, and all that’s happened in the intervening time, what jumped out at you seeing it now, having that distance from when you were working on it initially?

Moyer: I literally was blown away. I was watching this movie sitting next to my son and he turned to me during “America” and he said, “I can’t see everything. There’s just so much that’s going on, I can’t look at everything.” And he’s right. When people asked me about what it was like working on this, I tell them the production value of this was epic, it was just big. Remembering all the different parts of something like the “Gee, Officer Krupke” scene, we mix Steadicam and jib arm and different techniques. I’d just forgotten; I really have to see it again, for the same reason. I knew it was big when we were doing it, but then it went away for two years. Coming back now, I’m struck by everything: the music, the singing, the close-ups were just huge close-ups. The camera just kept pushing in and pushing in and pushing in. I think what you said, Mitch, was being taken aback. I certainly was taken aback. It was breathtaking. Having that disconnect between shooting it and seeing it, it was quite a surprise. It was almost humbling because I can’t believe I was able to be a part of this. I was just like, “There’s no way I did some of these things.”

Dubin: I think also, David, you were referring to it being pre-pandemic. When I watched this film, I’d say there was a certain melancholy about it because it was shot pre-COVID. We never thought about wearing masks, and it was at the time of life where we worked as we’ve always worked in our careers. We wandered around New York City and we went out to restaurants, Buzz and I would have steak dinners together, all these things that we took for granted that we can’t do right now. And especially the filmmaking process is really different than what it was then. I don’t think you could do a film like West Side Story in a pandemic environment. It was big. I mean, this is the perfect example of a big Hollywood movie: thousands of extras, closing off blocks and blocks of New York City streets, period cars, it was just big. Like Buzz, there are times when the camera pulls up and out and I go, “Holy cow! This is a big movie!” I don’t know if you could do that now. It makes me miss the days before COVID.

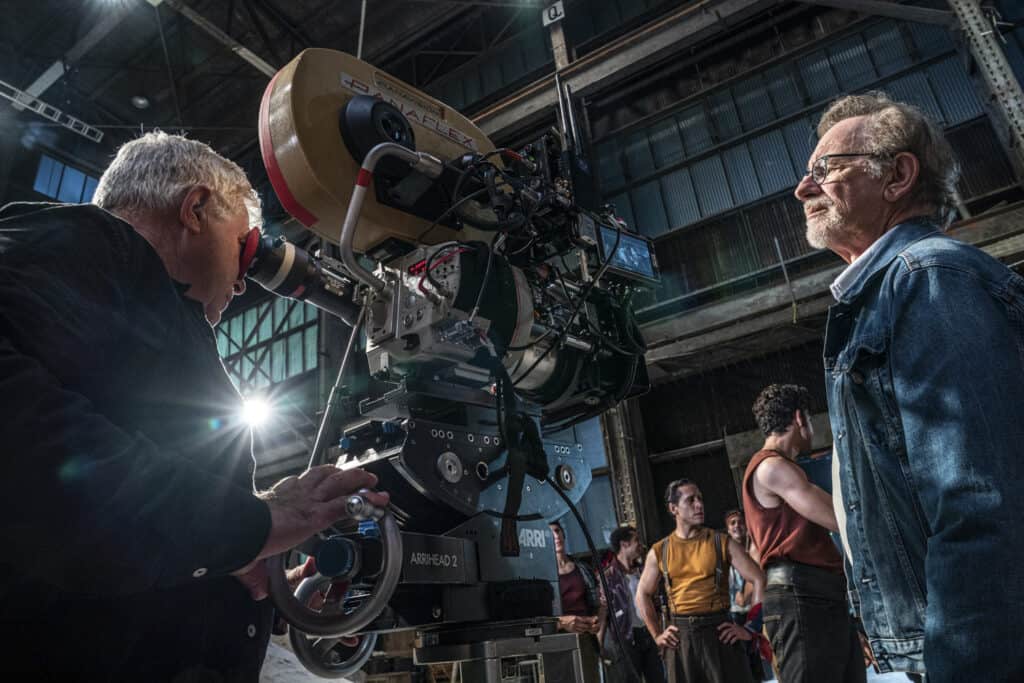

Mitch Dubin and Steven Spielberg on the set of WEST SIDE STORY

CO: Going back to something you were mentioning, Buzz, talking about the dynamic camera work and how there’s just more than you can fully see in an initial viewing. Thinking back to the earlier version of West Side Story, that film predated the Steadicam by almost 15 years. In it, a lot of the big musical numbers play out mostly in wide master shots with some minimal camera movement, but here, like you said, the camera work is so dynamic while still maintaining that classical feel. How do you think newer technology impacted the style of this film?

Moyer: I’ll speak for the Steadicam part and I think Mitch can speak for the Libra Head part of it and having the telescopic crane. Steadicam allows you to get in there close without the handheld feel. There are obviously shots in the movie that were handheld, and thankfully Mitch did the long hard ones, but with Steadicam there’s a freedom of being able to move the camera. There were a couple of moments I can think of where we took the Steadicam 180 degrees, [from] looking one way to looking the other way very quickly. The ability to do that—for example in the “Krupke” scene—was huge. It’s funny because Steven’s standing next to me describing the action. “They’re throwing the kids back and forth and Baby John’s getting thrown this way, then he gets thrown that way, then back this way, then you pan that way. And then what happens? Okay, okay, then you throw him that way, okay, then he goes that way.” And he looks at me and he goes, “did you get all that?” I said, “No,” and he says, “Well, fuck it, let’s just shoot it!” You’re so focused on everything in front of you, and the ability of Steadicam to be able to move that quickly and even the little nuances of just being a little more over or being more 50/50 depending on where the camera lands on the performers, positionally, I think that is very advantageous, certainly for dance in that close proximity. I think Mitch can talk about being able to use a Scorpio crane and being able to move smoothly on the dolly with the Libra.

Dubin: We use the camera in all different designs and configurations. But in terms of your original question, what the difference is technology-wise between the film from the 1960s and what we have available to us now—it’s huge. We had all different sizes of telescoping cranes that you can extend out, pull in, rise up, swing left and right to get these fast, low-angle moves. We used a stabilized head—mainly the Libra—on these telescoping cranes. We also put the Libra on the dolly to roll around in smaller sets. With Steven, we’re always inevitably doing shots that are 180-plus, sometimes 360-degree shots, so that you need to be on a remote head. We also did a lot of something that I’ve only done a couple of times before, but you can take the Libra Head controller, take the wheels off, and actually put it on your shoulder. They designed an eyepiece and handles for it, so I can actually do handheld work, but the camera is on the end of a 50-foot crane up in the air. It’s a pretty interesting tool to use a stabilized head as a handheld tool.

That’s all equipment that wasn’t available in the ’60s, plus, obviously, the visual effects that are in the film, like that opening shot. Another shot like that is the one that leads into the dance in the school gym. That’s two or three different shots that they stitched together; again they couldn’t have done that in the ’60s. That shot starts as Steadicam, bringing the actors down the hallway, then as soon as the doors open up, it transitions into a cable cam shot that goes up into the air and over to the other side of the gym. You see all the dancers, the set, the period costumes—it’s a spectacular shot. That’s one of the signatures of Steven’s movies: the camera starts tight, goes wide, but it doesn’t end there. It keeps going and ends up back into a shot that moves the story forward, [but] that’s not a big wide shot. In particular, this shot ends up with the joke of Officer Krupke holding the glass of punch.

John “Buzz” Moyer on the set of WEST SIDE STORY

CO: One of the most interesting things about this new movie is how it is in conversation with the 1961 film. I don’t think that it ever quotes shots exactly, but there are definitely visual connections. Talking about the dance in the gym, for instance, this movie uses lens flares to reference an optical effect that was used during the same scene in the original. How much did you look to the earlier adaptation to inform the camera work on this?

Dubin: We shot with Anamorphic lenses, which tends to create great flares, but some of the flares might have been supplemented by visual effects. But in terms of reference, when I first heard about this movie, my first reaction was why would Steven want to remake a classic film? I hadn’t seen West Side Story in years, so I revisited it and I was struck by how limited that film was cinematically. The music is great, the choreography is great, but it’s so different than what we did. When I watched the original film, I don’t think it held up very well. I think a lot of people might disagree with me, but at least cinematically, they filmed a Broadway stage musical. It’s nothing like what we did. Plus, I have to say, the story of West Side Story is still so relevant to what we’re going through today with all the racial issues and discord. It’s a story that’s still so relevant. I think it was important to retell it.

CO: Speaking to the differences between the two, you were talking about how the original film was shot in a much more theatrical way rather than cinematic. A bit like I was saying earlier, the dance sequences would take place effectively on stages—whether that’s a rooftop or gymnasium or whatever else—and you would watch it mostly in the master shot like you would a musical production. The original also had that more balletic dance-fighting, but here the choreography does really interesting things transitioning between dancing and fighting, sometimes even within the same shot. What went into blending those two visual languages together like that?

Moyer: All of the choreography was done months in advance. We would come in and the shots were designed around the choreography and choreographer would adjust things based on where the camera was at a certain part of the blocking. I think, in a lot of ways, that’s kind of out of our element or our decision making. We just try to carry out what is asked of us in the best possible way.

Dubin: On the note of the choreography, I had never done a full on musical before—I don’t know if Buzz had or not—but it’s very different language filming a musical with dance and singing, but especially the dancing. It was great! It was an amazing experience, and I loved it. It was a whole introduction for me into the world of dance. Justin Peck and his wife, Patricia, the choreographers, were wonderful. I loved working with them. They had never done a film before, at least not a big film like this, so they were really intrigued by our process. Steven will have his video village setup, and usually because I was on a remote head, I had my little video setup near Steven’s village. There’s a progression from people that are in Steven’s tent, because it can get really crowded in there, that they’ll wander over to my little mini video village. I loved it when Justin and Patricia would come and they would hang out with me because they were so intrigued by the process, and I was intrigued by their process. It was always a really interesting dialogue and conversation.

Then, on top of that, we would get cues from Steven—Buzz probably understood it better than I did, because he’s a musician—but it would be like, “Okay, Mitch on the downbeat of the third verse on the fourth stanza, I want you to whip pan over to this dancer leaping in the air.” I would say, “Okay, all right,” then I go back to my wheels and I have no idea what that actually meant. I’d screw up once or twice and I would have one of the choreographers stand next to me and that would help, or Matt Sullivan, the music supervisor, would sometimes say, “Okay, Mitch get ready, it’s coming up.” They might have to give me a little tap on the shoulder. Normally, as camera operators, we take visual cues—that’s how we work—but with dancers, because they’re so athletic, if I wait to watch a dancer jump in the air, I’ll always be late. Dancers don’t bend their knees and wind up to jump. They’ll stand there and all of a sudden they’re three feet in the air. So, it really does have to be based on music cue. The first couple times I tried it, getting instructions about music cues, I’d say, “Nah, that’s okay, I’ll just watch out of the corner of my eye and when I see that dancer jump, I’ll just whip pan over.” It never worked, I was always late, so I had to learn much more about music.

Moyer: I had an unfair advantage in that when I was in fifth and sixth grade—and past that, and before that—I was actually a professional dancer. I did summer stock theater, I was an equity performer, and I was 10 years old when I did Oliver! with Vincent Price. Vincent Price played Fagin, and I was one of Fagin’s boys. So I was a professional equity dancer, and then the next year I did Peter Pan with Sandy Duncan before she went on Broadway. When someone says, “five-six-seven-eight,” I’m ready, I am up, I’m there. So, I had a real advantage with that because I could see a routine and quickly know the points. Not being dolly or crane-bound, I had the benefit of being mobile. Mitch can only pan or tilt so much when he’s on a crane or a dolly, so if the dolly is late or the crane’s not in the right position, the shot may not be as planned. I have Joaquin [Padilla], my dolly grip, spotting me, and getting me to the marks, which also allowed focus puller Tim Metivier to be sharp.

Mitch Dubin on the set of WEST SIDE STORY

CO: Mitch, I know you’ve been working with Spielberg for many years now and he’s been threatening to do a musical for a long time, what was it like working with him on both his and your own first musical?

Dubin: Yeah, I’ve done 18 movies with Steven now. He’s always talked about wanting to do a musical, and I can’t imagine a director that’s more suited to doing a musical than Steven. Especially something like West Side Story. He was really prepared; obviously, he knows the music inside and out. Steven works a lot off the cuff. We storyboarded some of the visual effects and complicated shots, and they did a lot of rehearsals with the choreography, but for a lot of the scenes, he’d come on the set and he’d figure it out.

But for a musical—and why he’s so well suited to it—is because he loves big, sweeping shots, and cameras that never stop. Even if we know there’s going to be coverage in the scene, he still loves to shoot masters that cover the entire scene. It makes it fun, and it’s challenging for us as camera operators to do that. It was a bit of a learning process for me doing a musical. Like I mentioned before, there are a different set of rules, like you don’t want to cut dancers’ feet off. When you’re doing a narrative, dramatic film, there are preset sizes. You know in a wide shot you’re going to see things, but the feet are not your first consideration. But in a dance musical, it’s so important to see their feet. I had to get reminded a couple of times, “Mitch, you cut the feet off,” so I’d do it again. It’s always so inspiring to work with music. All the actors sang their own songs, and they sang them live as we filmed them. There was a recorded version of the music in everybody’s ear. I always had the music in a comtec in my ear, because everything was so musically motivated. It was quite an experience to be filming on the set with the actors singing, with the music, with the dancing. It was fun.

CO: In The Hollywood Reporter’s cinematographer roundtable, Janusz Kamiński talked about the importance of creating a heightened reality for a musical like this. I think his exact quote was, “not fantasy, but just the world of the musical.” Obviously, that goal is shared across the whole production, but specifically for operating. How do you find that place visually, that’s not so distant from our own world, and yet still a place where people singing and dancing their emotions feels true?

Moyer: One thing I took away that I thought was really interesting is the flares. It almost felt like I was at a theater watching a live performance with lights in my eyes. Also, there were a lot of higher shots, from above looking down, and that also puts you in the theater. A lot of people sit above, and they see most performances from kind of wings and they’re up high, so they’re seeing the performance [by] looking down on it. It’s a very comfortable place, you’re comfortable with it, you’re familiar with it. When you’re going from a jib or crane, going from a low wide shot that then rises up and pushes in for a piece of dialogue, you’re not worried about stacking because you can have actors and dancers placed to fill in that part of the frame. You’d be overhead in a bird’s-eye view and still be able to see all the people reacting, still see the feet of the actors because you’re over their heads, and still be close enough to the person in the foreground to get their reaction, their emotional response. When you’re doing it and you’re seeing it live, you don’t realize the effectiveness of it until you cut together four or five shots that take you through all the different points of view.

Dubin: I would add, from my point of view, that’s the difference between a camera operator and a cinematographer. Janusz, during his prep, will come up with a lighting scheme, a color palette, filter choices, and all sorts of decisions he can make in advance to create a certain look to the film. What was the term you used, a heightened reality? That’s the job of a cinematographer to come up with these looks, but as a camera operator, you cannot have any preconceived notions about anything. You must be open, accessible, and responsive to the moment of creation when it happens inside your frame. If I start thinking about, “I need to frame that more to the right because that will make it look more like heightened reality,” I would be dead in the water on day one. You just can’t think that way. So, all that stuff about look and heightened reality, that might be done in pre-production, but when you’re actually shooting, you have to be able to execute the shots gracefully and cinematically, but it has to be without thought sometimes. It’s like this gut, instinctual, intuitive response.

I will say, on this project there was a different reaction for me than what I normally have when I’m behind the camera. Like I said, our process as camera operators is very intuitive, very instinctual, and responsive, but on West Side Story, there were times when I was operating a shot, and all of a sudden I would feel my chest tighten up and I’d realize, “Mitch, are you going to cry? You can’t cry, you’re in the middle of a shot!” The actors are singing some very powerful scenes, and they gave it everything as performers. I would feel this incredible emotional response. We’re behind the lens and my eyepiece is fogging up. It was a very intense emotional experience for me as a camera operator, and I think for Buzz as well. I’ve done a lot of dramatic films in my career, but I don’t ever remember being so emotionally affected as I was on West Side Story.

John “Buzz” Moyer on the set of WEST SIDE STORY

Moyer: One of our first few days of shooting, we were at the “Cool” set. I had a low, long lens shot and Mitch had a high, wide shot. It was after the gun was tossed between them, the Jets are running off the pier. I think it was the third take, Sean [Harrison Jones], the Jet on the left, took a header and skidded across the ground. He got up and he was obviously upset with himself for failing that moment for everybody else. That was emotional for me. To see the desire [that] these truly dedicated performers had to do the best they possibly could, for not only the history of West Side Story, but for the ongoing appreciation of the story. That was something that stuck with me. A number of people asked if he was okay. “I’m fine! I’m fine,” he said smiling, “I’m sorry! I’m so sorry! Please let’s go again!”

The passion that was brought to the set by everybody was inspiring. The joy and the camaraderie of the dancers, and the crew putting out everything. We were shooting on days when temperatures reached 115 degrees, and the actors and dancers were giving everything. Janusz had at one point, by my less-than-stellar math, 270,000 watts of light illuminating a city block. The music would start and from off-camera a group of 30 dancers filled the frame instantly. Everyone was on point and wanting it to be perfect, which was very, very powerful. Being with the Steadicam, being in it, being close when Rachel [Zegler] and Ariana [DeBose] are singing in front of me. I could feel their voices—that’s how loudly they were singing. It was really an emotional experience. During “A Boy Like That,” around the bed, when Rachel was pouring her heart out, I had the Steadicam over Ariana slowly pushing in to a closeup. There was a moment when I could not see the monitor through my emotions. Those are good days, ones to remember fondly.

Dubin: I have to say, I am really, really proud of this movie. I’ve done a lot of movies in my career, but this one really is just a synthesis of so many great things. History and the tradition of West Side Story and the performances and the entire crew being so dedicated to it. When you see the film, it just all shows. In regards to my work, I am very proud of it. The camera is a really important part of the story. I think the film looks great, and Buzz and I did remarkable work. I hope that all of the readers of this article enjoy the film as much as we enjoyed working on it.

Mitch Dubin on the set of WEST SIDE STORY

CAMERA DEPARTMENT

Janusz Kaminski—Director of Photography

Mitch Dubin—Camera Operator: “A” camera

John S. Moyer—”B” Camera/Steadicam Operator

Truman Hanks—Camera Intern

Connie Huang—Second Assistant Camera: “A” Camera

Cornelia Klapper—Second Assistant Camera: “B” Camera

Brendan Lowry—“A” Camera Dolly Grip

Tim Metivier—1st AC “B” Camera/Steadicam

Joaquin Padilla—B Dolly Grip

Dave J. Ross—Film Loader

Pierson Silver—Libra Head Tech

Mark Spath —First Assistant Camera

Niko Tavernese—Still Photographer

Camera Operator Winter 2022

Above Photo: Mitch Dubin, SOC, on the set of WEST SIDE STORY.

Photos by Niko Tavernise

Watch Now:

MItch Dubin, SOC, and John “Buzz” Moyer, SOC, introduce the Interview on West Side Story

TECH ON SET

Panavision Millennium Camera

Libra Stabilized Head

Handheld Libra Controller

45-foot Scorpio Crane

Chapman/Leonard Hybrid Dolly

Chapman/Leonard PeeWee Dolly

Heavy Lift Drone with RED Digital Camera

Sachtler/ ARRI Artemis Steadicam

Tiffen Master Series Arm

Tiffen Exovest

Betz Wave 1 for one VFX shot

INSIDE SCOOP

In a conversation with the DGA’s “Director’s Cut” podcast, Steven Spielberg said he worked out the blocking for the “Gee, Officer Krupke” number while recording rehearsals on his iPhone.

In addition to West Side Story, Buzz Moyer has also worked on a few musical and dance movies including reshoots on Jon Chu’s In the Heights, which shot principal photography in New York a few blocks from where West Side Story was filming.

Steven Spielberg had publicly expressed a desire to do a musical as early as the 1980s. In an interview with Total Film magazine in 2004, he specifically said he wanted to do an “old-fashioned” musical like West Side Story.

According to Steven Spielberg, 50 members of the cast of West Side Story had never acted for the screen before, including stars Rachel Zegler, Ariana DeBose, and David Alvarez.

RELATED CONTENT

Mitch Dubin, SOC

Learn more about Mitch’s career and projects at IMDB.com

Membership Content Portal:

Creative Spotlight on Fargo, discussing his work on the project

John “Buzz” Moyer, SOC

Learn more about Buzz’s career and projects at IMDB.com

Membership Content Portal:

John “Buzz” Moyer, SOC & Lisa Stacilauskas, SOC: Hosting the Inspirational Roundtable

BEHIND THE SCENES

Select Photo for Slideshow

Mitch Dubin, SOC

Mitch Dubin’s first job in the film industry was as a post-production PA on Apocalypse Now at Zoetrope Studios in San Francisco. During additional photography of The Black Stallion and Apocalypse Now, he realized working on the set, behind the camera, was where he wanted to be. Mitch worked his way through the ranks of the camera department until he settled into the job of camera operator. Thirty-five years later, Mitch still loves his job. He has been fortunate to work on many great films with exceptionally talented crews. Every project has been a labor of love that has made his life in the film industry a wonderful adventure.

John “Buzz” Moyer, SOC

John “Buzz” Moyer began his career after graduating from Ithaca College in 1986. Starting in the corporate and commercial world in Pittsburgh, he went on to features and television in the Grip department and moved into camera. “Every day was a learning experience, and eventually provided the funds to purchase a Model 2 Steadicam in 1989, which was a dream of mine since seeing Wolfen in College.” Buzz built his skills and client base and, after the required “10,000 hours,” continued relationships that would lead to more and more opportunities to learn and understand the role of a Steadicam operator and, more importantly, the responsibility and role of a camera operator. Thirty-two years later, Buzz has been fortunate to work with a list of respected DPs and directors. “I am very lucky to be here. I am thankful for all the mentors along the way and those that trusted me to do the job.” Buzz hopes he can do the same for many who aspire to be a camera operator.

David Daut

A writer and film critic for close to ten years, David Daut specializes in analysis of genre cinema and immersive media with bylines at Lewton Bus, No Proscenium, and Heroic Hollywood. David studied at the USC School of Cinematic Arts and currently works as a freelance writer based out of Orange County, California.

.