SOCIETY OF THE SNOW

NO EASY SHOTS

A Conversation with Juanjo Sánchez, SOC & Manuel Branáa, SOC

By David Daut

Nominated for Best International Feature at the 96th Academy Awards and winner of the SOC’s Camera Operator of the Year in Film, Society of the Snow recounts the harrowing true story of the survivors of Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571.

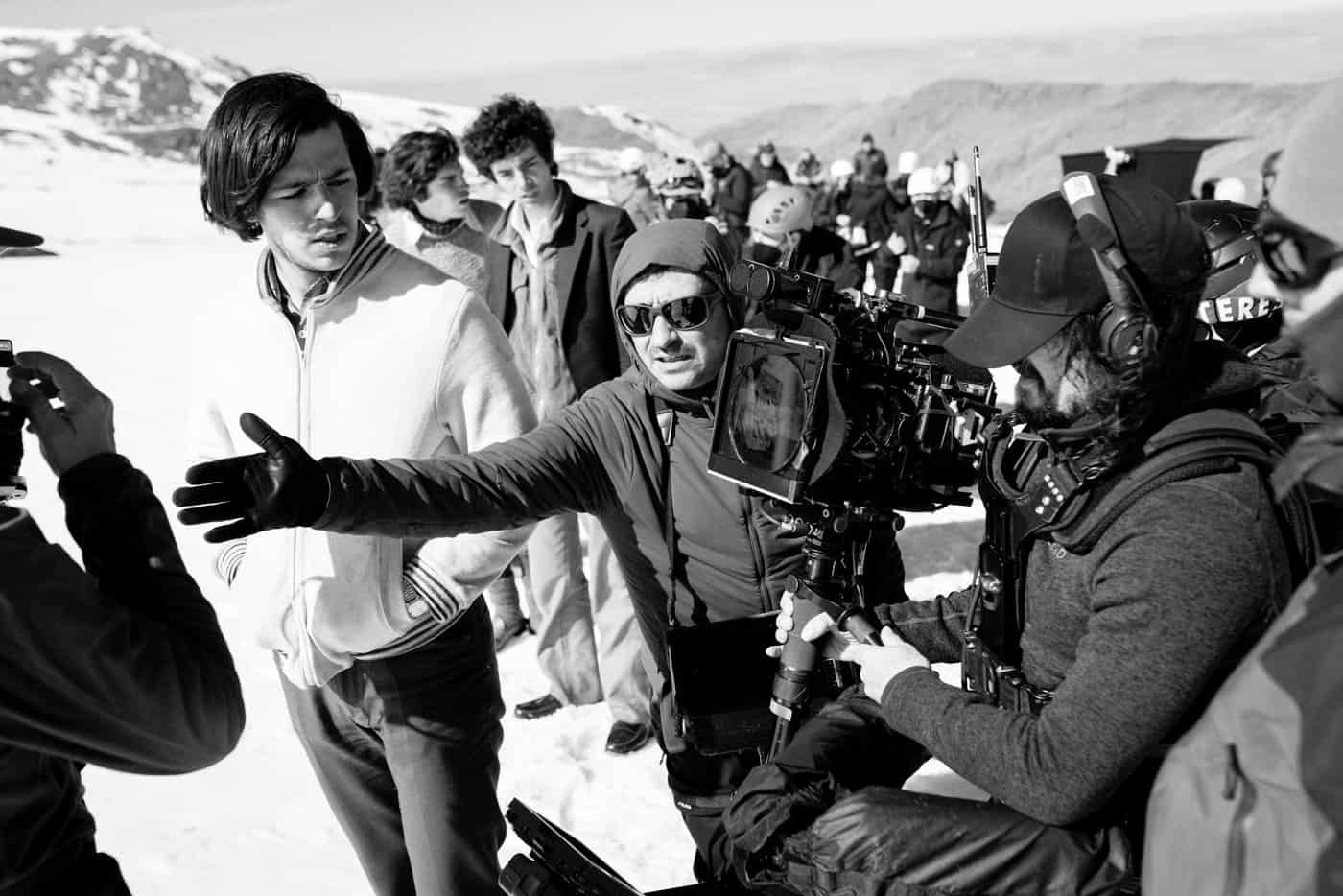

Camera Operator had the chance to speak with A camera operator Juanjo Sánchez, SOC, and B camera operator Manuel Branáa, SOC, about working on the film—from shooting in the four different sets used to recreate the fuselage of the crashed plane to what it was like working with the young ensemble cast that portrayed the stranded rugby team. We also discussed their recent wins for Camera Operator of the Year in Film and what that recognition has meant for their careers.

In October of 1972, a flight carrying the young members of an Uruguayan rugby team crashed in the midst of a storm, leaving 29 people stranded in the Andes mountains with no hope of rescue until the snow thawed. For 72 days, the survivors of the crash had to endure extreme cold, brutal storms, starvation, an avalanche, and the mental toil of isolation as they work together to stay alive and ultimately escape the glacier in search of help. Society of the Snow is directed by J. A. Bayona from a screenplay by Bayona, Bernat Vilaplana, Jaime Marques-Olarreaga, and Nicolás Casariego. It stars Enzo Vogrincic, Agustín Pardella, Matías Recalt, Esteban Bigliardi, Diego Vegezzi, Fernando Contigiani García, Esteban Kukuriczka, Francisco Romero, Rafael Federman, and Valentino Alonso.

Camera Operator: So, Society of the Snow is obviously based on a true story, the unimaginable experience that this team went through trying to survive in these horrific circumstances. I understand that for at least some of the film you shot on location at the actual crash site. What was it like recreating the events in the location where they actually happened?

Manuel Branáa: I didn’t actually go to the Andes site. There was a very limited, small splinter unit that went out there. That unit was a more specialized team with alpinists along with the DP, the director, and the actors. Juanjo, did you go to the Andes?

Juanjo Sánchez: The site of the crash is called Valle de las Lágrimas—the Valley of Tears—the actual shooting there was very limited. It was mostly drone footage and plates for CGI backdrops that would then be used afterwards for set extensions. I did shoot some scenes lower in elevation in the Andes, when they were doing that final hike to find help, when they met the “arriero,” the guy on the horse, the first person they see.

Branáa: I remember them saying, they went there for a week with a very small team and they had an incident. They went on the anniversary of the crash, and there was a huge wind that blew away all of their tents. It was like a godly sign that they shouldn’t be there.

CO: Oh, wow! That’s nuts.

Branáa: That’s the story I got, anyway. But yeah, it was a very specific shoot and very hard to get up there, so they took alpinists with them.

Sánchez: They went to the Valle de las Lágrimas twice because the first time they didn’t have enough snow to shoot. They went back one year later, but it was just the VFX crew, the DP, and the director.

Branáa: Sorry if that’s an underwhelming answer. We weren’t there!

CO: Well, let’s move on to some stuff that I believe you were there for: the actual fuselage set itself. A lot of the action of the film obviously takes place in and around the fuselage of the crashed plane. I understand there were three different sets built for that. What was it like shooting on those sets?

Sánchez: There were four, actually! There was a fourth for shooting the plane crash at a stage in Madrid.

Branáa: During principal photography, we were in Sierra Nevada, Spain. This was about four months that we were there. We had three sets that were all replicas of the fuselage as it was after the crash. When the fuselage came to a stop after the crash, it was turned at almost 45 degrees, this made it really complicated for us to shoot.

Sánchez: And it was slippery.

Branáa: The first set was tucked in the middle of the mountains. It took a lot of work to get there every day. We had to take a van to a ski lift to a snow plower. The ride on the snow plower took about 40 minutes with the whole crew crunched in, legs interweaved, with our ear buds in the morning. The view was very pretty, though—we got to see the mountains in the morning and at night. That set was used mainly for shooting exteriors. They did a lot of set extensions, but they used these exteriors for the most part. It was very bare bones in terms of grip and electric. We had a GF-8 crane and Juanjo operated the Steadicam up there, but barely any lighting. It was very natural. It felt like the most realistic shooting conditions and the most we were immersed in the situation.

The second fuselage was on a stage that was built on a parking lot at the bottom of the mountain. The stage was built by Germans engineers to spec for this shoot. The stage was good, but sometimes the winds would pick up more than 70 miles an hour, and we would have to evacuate. That stage had a platform that they then covered with fake snow. The fuselage was elevated off the ground so they could access it from the bottom, which was useful for the avalanche scene, and then it was all surrounded by 100-degrees-worth of LED screens. Those LED screens had the mountain plates that they shot in the Valle de las Lágrimas. They had all sorts of images so they could constantly be projecting them depending on what the background needed to be. That set we used mainly for interiors.

Sánchez: In the stage set we used many different tools: a lot of Technocrane, handheld and sliders, and dollies—mainly from the outside looking in—and Steadicam very seldomly inside.

Branáa: It’s a very confined space. There were 25 actors, give or take, all in there with us. It was very realistic, so the space was like the way the real plane was. The floor had old, airplane carpeting. There were a few different things they used for snow, sometimes it would be soap, sometimes it would be little plastic flakes, and it made the carpet extremely slippery. We were constantly grabbing onto things, operating with one hand. We constantly had to ask the grips to drill in pegs of wood for us to put our feet on.

Sánchez: It was very hard because the Technocrane had a remote head and I was further away, outside of the platform. I like to operate in a black box. Completely dark to really isolate myself and be with the monitor. I didn’t have any idea where the camera was in terms of the spacing with the rest of the plane, so I had to trust Salva [Castellarnau, key grip]. He was in charge of the head and where it was, so it was a really good connection between the two of us to put that head in that little space in between actors without hitting anybody in the way.

Branáa: For some moments, it was really epic and slow and big, and other moments, it was very crunched up and natural being among all these people just tucked in there.

Then the third set was on a backlot almost an hour down the mountain. It was not that cold, so it was not snowy down there—it was an olive orchard, actually. They built a bigger platform there.

Sánchez: I think it was three meters high.

Branáa: Yeah, three meters high and 100 meters by 100 meters in dimension. It was used a lot for when, after the avalanche, the plane got buried in the snow. They had a hydraulic lift that would take the plane up and down so that it would mimic how deep in the snow it was supposed to be. We did some bigger shots there; a lot of second unit was shot there, a lot of the storm scenes, because they had more control over environmental effects. This one had the most background replacements because there were no mountains. It was a lot more CG intensive. I didn’t go to the backlot that much.

Sánchez: I went just one time there. Just one day from what I remember. It was mostly second unit.

Branáa: There was a lot of second unit work. The second unit DP, Culaca [Gerardo González], he’s also from Uruguay, same as Pedro Luque. I’m from Uruguay, the rugby team were from Uruguay, so there was a connection going on there. And then Tebbe [Schöningh] was the camera operator for the second unit. They were all putting their hands in there in so many different ways. Then the fourth set that Juanjo was talking about, that one was in Madrid. It was used many months after we wrapped principal photography.

Sánchez: Just used for one week. Five or six days of shooting.

Branáa: And that was the actual plane crash. So, it was not the same fuselage, exactly. It was like a sawed-off version of the cabin. They had different forms of it depending on the effect they were trying to do. It was also on hydraulics, so they could recreate the more intense movements of what the crash was like for the actors inside, so they could get the gravity correct. The rest was just parts of walls so they could see things falling apart. Juanjo was there, I didn’t get to go shoot that part. It was a lot of practical effects and CGI.

Sánchez: Sometimes the gimbal with the plane on it was at a 45-degree angle, so it was hard. We had to be harnessed in.

Branáa: There was a second unit and third unit, there were alpinists. So, when it comes to camera operating, we kind of held the main position, but there is so much material that was shot by other people. There were drone operators. There was Gerardo González, who was the second unit DP, and he’s also a Steadicam operator, so he did some Steadicam. There’s Tebbe who was the operator for the second unit. And the grips themselves. So, as far as camera operating, you know, we dictated the tone, but there were so many other people that were also doing the same work and they’re all sprinkled through.

Sánchez: The whole crew really supported us.

Branáa: Personally, the people I want to put out there the most are our ACs. Guillem Huertas, he’s a master of 1st AC-ing because of the complicated array of things he had to deal with. Not just focus pulling, but organizing the materials that had to go onto these three, sometimes four different sets. A logistical nightmare of how to get the gear from one place to another in a snow plower. Plus the lenses got destroyed throughout the shoot, so they were shipped back and forth from Panavision in France because they had to clean them from the snow. Guillem Huertas was just a genius. He was 1st AC for Juanjo. Ana Sánchez [Tejera], she’s incredible too. She’s like a sergeant, a diligent soldier. She was the 2nd AC for Juanjo. Helga Otero and Francesc Olivé were B camera 1st and 2nd ACs. I couldn’t have done my job without their support throughout the film.

Salva was the key grip, he made possible all the complicated rigs that we needed to build, sometimes building cranes in the middle of the mountains. We had snow storms that would cover all the gear, and they literally had to dig out the gear.

Sánchez: Maybe three meters or more of snow.

Branáa: So, there were not just technical challenges and typical pressures of being on set, but also the crazy weather conditions that would throw us these curveballs constantly. We had a storm that came from the Sahara desert that turned everything orange. It was dust particles, and the whole snow became orange one day. Apparently it happens every year, and it was a huge challenge. Not just to our eyes and the pollution that it created to breathe, but also visually, how do you deal with that? Of course, that was more a production issue than camera operating, but we’re all on the same team.

CO: What were some of the other challenges of working on this film? Are there any particular shots or particular moments that spring to mind?

Branáa: Juanjo, you’re the one that tattooed the coordinates of the mountain.

Sánchez: [Revealing a tattoo on his right bicep] These are the coordinates of the Sierra Nevada set where we shot. I have a philosophy about operating camera: I think an easy shot doesn’t exist. Even an insert can be very difficult to shoot. I can’t say there was one shot in particular or one thing that stands out as far as difficulty, because what made it difficult were the general conditions. It was the altitude, the snow, the cold, the terrain in general. Those conditions applied to the whole shoot and slowly wore you out in many ways.

Working with director J.A. Bayona, he’s a very demanding director in his own way. He’s in his own right to do so, because he’s a perfectionist, and that’s needed for this kind of work, but it makes the work very detailed and demanding. If I had to pick one thing that stands out, though, it’s the sequence that we shot for when they were buried in the avalanche.

Branáa: For me, what made it complicated was reinventing the visuals of the set. We were shooting inside that fuselage for four months, so it was trying to come up with different ways of telling the story that didn’t look like it’s always the same shots. Keeping it interesting for the viewer while also matching the story tone. There were a lot of different camera tricks and different things that we used to find interesting visuals in that same space over and over. And yeah, definitely working with director, Jota [J.A. Bayona]. He’s a genius, but he’s definitely “exigente.” He’s someone who wants a lot out of you and holds everyone to a high standard.

The handheld work was very hard. Inside that fuselage, it was really complicated. Sometimes you would have to get in almost contortionist positions that were not very comfortable for a long time.

Sánchez: I remember your shot with the EasyRig.

Branáa: At one point, I was in a rush to set something up and I decided the best way to do this shot was me on an EasyRig. It was a top-down shot of someone, and I’m holding the camera with my arms extended out in front of me. I just didn’t think it was going to be 40 minutes of someone dying. You never know where a scene is going to go emotionally.

Sánchez: I had my camera on a Steadybag and was looking at Manuel suffering, just trying to keep his balance. Poor kid!

Branáa: It was a delicate moment of someone dying. There are a lot of deaths in the film. You start with 25 people in that plane, and they gradually kept dying. There were a lot of these really delicate moments and sometimes you just had to hold it. It was very demanding for my back, but you have to stay there until the director calls cut, because you can’t interrupt that kind of moment.

CO: So, on that note, what was it like working with J.A. Bayona? I know you’ve both worked with Pedro Luque before, but this was your first time working with J.A. Bayona. What was it like kind of taking that existing working relationship that the three of you have and matching it up with a new director?

Sánchez: Yeah, we worked with Pedro on Don’t Breathe 2 shooting in Serbia. As camera operators, we need to be chameleonic—we have to adapt to DPs and directors and a new team every time. Jota has a very clear vision of what he wants in his movies. He’s very focused on what he wants to get out of it, so we’re very much marching to the beat of his drum. Pedro’s really great at adapting and morphing with the style of a director, so he really was able to follow Jota’s lead, but still keeping his way of lighting and his own personality in it.

Branáa: Jota came from doing Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom and The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power before this, so he was coming from more of a blockbuster sensibility. I remember in the first couple of weeks, he was trying to define the camera language of the movie, because he wanted to do something different from that Hollywood look he came from. He was trying to experiment with some new ways of doing camera storytelling, and we had some conversations with him. It was an interesting experimental moment at the beginning. Do we do a lot of cranes, a lot of dolly, a lot of more controlled stuff, or do we just go with more 12mm handheld craziness? We were going back and forth, just experimenting.

Eventually, like everything in life, I think it landed on a healthy middle. There was a bit of both worlds. We had a lot of cranes, but we also did a lot of handheld. I don’t think he leaned into any extreme, but it was an interesting discussion for the first part of the movie in which we were all figuring out what makes sense here. What is the correct tone and language? I really appreciated that because I like the idea of the movie generating its own personality as it starts, not just predetermining this is what the movie is regardless of what the conditions are, what people are feeling. We were experiencing it and adapting to that.

Sánchez: We were allowed and encouraged to talk to Jota directly and have conversations with him as camera operators. Sometimes that can be a bit tricky politically, but I think Jota enjoyed that a lot. He’s very hands-on in terms of the camera. So, while Pedro sometimes was lighting and doing his thing, we were able to talk to Jota and work out the kinks of the shot or discuss how we’re moving and how we need to do it. That really allowed for a lot of fluidity and not having that sort of triangular communication that sometimes can be confusing.

CO: I wanted to jump back to something that you both touched on a little bit, but just the idea of this large ensemble cast that you’re working with. What was that like as camera operators?

Branáa: It was very interesting. These were mainly first-time actors—they may have done smaller theatre or little indie films in Argentina and Uruguay. The cast was mainly Argentinian and Uruguayan, which was meant for a more realistic experience because of their accents and sensibilities. They were also very young—between 20 and 25—and they were just extremely excited. They were this herd of Argentinian kids that were constantly playing around and being funny. A lot of camaraderie between them. So, that was the air that existed on set. It was very joyful. People say, “Oh, wasn’t it depressing with all the dying and the cold?” No, actually, they were in a constant party, these kids. They weren’t being disrespectful to what happened, but they were just so happy to be there that you could sense that. They just permeated the set with that energy.

Sánchez: They had two acting coaches that were really great. One, [María] Laura Berch, became sort of like the mom of the kids. She was really warm, and they did, I think, over a year of pre-production for them to get into the roles and understand what it meant to be there. That included a lot of different exercises. They did breathing exercises, a lot of sounds—we had a giant gong on set. They did these exercises a lot before takes, so we were always part of this just by nature of being there. Sometimes they would happen right before the director called action. They would go into these breathing exercises—in India, they call them Pranayamas—and they would do it as a group. Twenty people start breathing hard for three minutes.

I also wanted to note from the previous question, Jota would play music on set very loud. That was very important for me for operating camera, because I put my eye on the viewfinder, and I used that music to keep my mind inside the camera.

Branáa: Juanjo especially, but we both were very transported by the music. It was very score-like. Very intense, deep, and emotional music, so it really dictated the move of the cameras, speed and the motion that we were going for. Juanjo is very much in touch with his emotions, so when he’s operating, he really feels heavily what’s going on on the screen, and the music really just pushes that further for him. I know because I was over his shoulder, seeing him operate the wheels every time. I learned a lot from him.

We had the music and the breathing right before takes, so we were somewhat a part of this group of kids that were there in the plane. Sometimes we were just tucked in there with the cameras, just sitting and waiting for this intense energy to rise before action. It was an incredible experience of being almost a cast member as the camera operator. We were very close with all of them. There was a lot of support, like in the avalanche scene. We could barely move, we had very little space, so the actors would actually help us to not fall into holes by pushing us and moving us in the right direction. There was a lot of communion with these actors. It was great having all of them around. I think a lot of camera operators say that you have to be a performer or a cast member when you’re operating.

CO: Since this film has come out, it’s gotten a lot of really positive response. Nominated for Best International Feature at the Oscars, and the two of you were nominated for and then won Camera Operator of the Year in Film. Can you talk a little bit about what it’s been like seeing the reception to this film and then personally, for the two of you, getting that nomination and then the subsequent win for Camera Operator of the Year?

Sánchez: When I got the email—it was a pre-nomination email from SOC—I was eating at a restaurant with some friends. I jumped off my chair! I was extremely excited. Nobody could hold me down. Then, when I got the actual nomination, I was on my way to the airport to the Canary Islands for a shoot. I was so excited, I hugged the driver and told him I was nominated and we celebrated.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to go to the award ceremony because I wasn’t able to get my ESTA certificate in time. The whole situation was kind of rushed. I was on a shoot, and they were not going to let me take a break, but then last minute they decided that, yes, I could go. I tried to get my ESTA, but it didn’t arrive in time, so that meant I had to watch it with my mom in my pajamas, which was a very curious way of going through the experience. It was different, but it was also very beautiful to have that way of doing it.

Branáa: It was also very late for him, because it’s nine hours ahead. It was, like 4 a.m. I was able to go and I tried to connect with him as much as possible and do FaceTime to show him the award ceremony.

Sánchez: I’m extremely thankful to the SOC for giving this award. For me, it’s the best achievement in my lifetime. I’m so grateful and happy to have received this honor. I’ve been operating for more than 30 years, and this is just a dream come true as far as recognition. I was able to come to L.A. afterwards, so Manuel and I did a lot of going around. This has opened a lot of new doors for connecting with people there. I have a lot of heroes that work in Los Angeles, so being able to connect with those DPs and other operators is a process that is happening now.

Branáa: For me it was the same but more extreme, because I haven’t been operating for 30 years, so all of a sudden I had the door opened to all these people who had no idea who I was. It’s been very important to receive these connections from all these masters of camera operating, to have them come to me and congratulate me and have a conversation with them about film and what camera operating is. It has been a beautiful welcoming into the Society of Camera Operators, of which, like Juanjo, I am now an Active member.

Above Photo: Shooting SOCIETY OF THE SNOW in the Sierra Nevada mountains of Spain

Photos courtesy of Netflix

TECH ON SET

ARRI ALEXA LF & ALEXA Mini Cameras

RED Dragon Camera

DJI Drones

GoPro

Leica SL2 Camera

Sony FX3 Camera

Panavision T Series & Panaspeed Lenses

Laowa 24mm Macro Probe

Technocrane 45

Fisher Model 10 Camera Dolly

MovieTech MT 400 Heavy-duty Crane

GFM GF-6 Crane

Mini Scorpio Stabilized Head V

DJI Ronin 2

GPI Pro 2 Steadicam

RELATED CONTENT

Watch the Trailer for Society of the Snow

Juanjo Sánchez, SOC

Learn more about Juanjo’s career and projects at IMDB.com

Manuel Branáa, SOC

BEHIND THE SCENES

Select Photo for Slideshow

SIGN UP FOR THE FREE

DIGITAL EDITION OF

CAMERA OPERATOR

Click Here

Juanjo Sánchez, SOC

Juanjo Sánchez, SOC, has always been enamored by music and cinema. He began his academic career thinking of becoming a sound mixer, but soon into the school program he looked through a viewfinder and thought, “This is what I want to do for the rest of my life.”

In 1992, Sánchez began to work as a camera operator on commercials and documentaries, but what he truly desired was to shoot narrative films. In 1999, he finally had his chance to work as a Steadicam operator and, ever since, Juanjo has been traveling the world looking through a camera.

Sánchez also teaches camera operating and Steadicam seminars at Escuela de Cine de Madrid (ECAM), and at the Instituto del Cine Madrid (ICE). Juanjo has been an Active SOC member since 2017.

Photo by Pablo Romero

Manuel Branáa, SOC

Manuel Branáa, SOC, moved from Uruguay to the United States in 2008 in search of a career in the arts. After stumbling into a film analysis class, where he first studied Hitchcock’s Rope, he was captivated (or held captive) by the relentless yet magical world of film.

Years later Branáa was fortunate to cross paths with Pedro Luque, who became a mentor and a friend. Since then, he has operated and photographed multiple projects around the world. Because of his love for the outdoors, Manuel accepted the invitation to schlep a camera through the icy Sierras to be part of The Society of the Snow for five months.

Branáa looks forward to continuing on the path of sore shoulders, physical therapy, and elevating storytelling for years to come.

Photo by Martin Piroyansky