The Old Man:

Not Moving the Camera

A Conversation with Paul Sanchez & Hilton Goring

By David Daut

Coming on the heels of their nomination for Camera Operator of the Year in Television, Camera Operator got to talk with the operating team of Paul Sanchez and Hilton Goring about their work on the series—work that was often defined not so much by how the camera moved, but instead how it didn’t. In the conversation, we discuss The Old Man’s unique style, shooting the car chase sequence from the season finale, and the dynamics of working as an operating team.

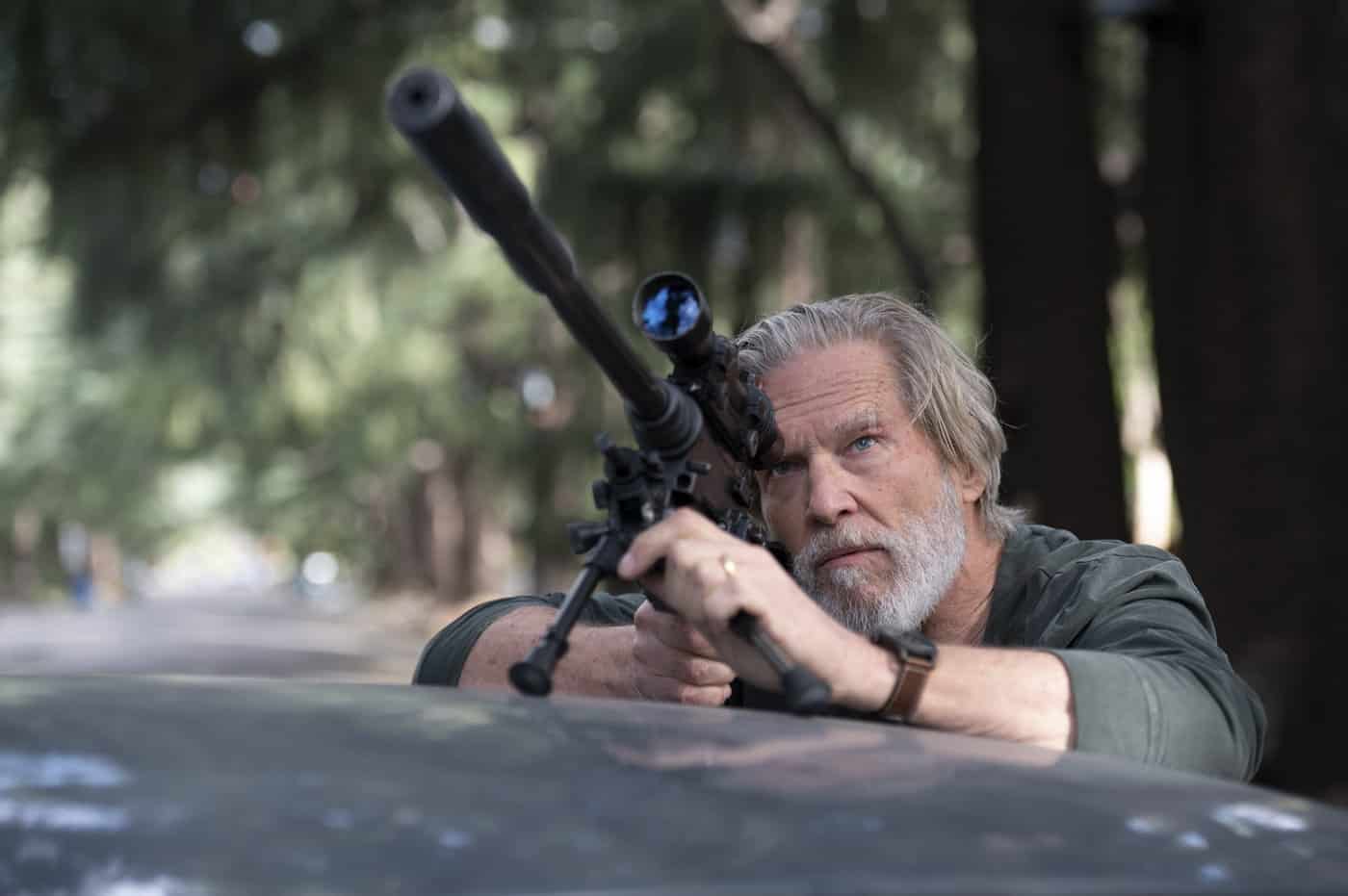

For his first leading role in a television series, Jeff Bridges stars as a man named—as far as we know—Dan Chase, a former covert operative for the CIA who has spent years living off the grid, hiding himself and his daughter from the fallout of a 30-year-old job gone wrong. Decades after being disavowed by his government and forging a new life of hiding and isolation, Dan Chase once again has to employ his training as a covert agent when his former partner, Harold Harper, is tasked with bringing Chase in at the behest of an Afghani rebel leader with whom the two men have a complicated history.

The Old Man was created by Jonathan E. Steinberg and Robert Levine based on the novel by Thomas Perry and stars Jeff Bridges as Dan Chase and John Lithgow as Harold Harper alongside Alia Shawkat, E.J. Bonilla, Gbenga Akinnagbe, Bill Heck, Leem Lubany, and Amy Brenneman.

Paul Sanchez, SOC, operating on THE OLD MAN

Camera Operator: To start with, how did you two come to get involved with this project?

Hilton Goring: My connection with the project was through the unit production manager, Sarah Donohue. She called me, and I met with Sean [Porter]. Once I met with Sean, we had a good chat, and I got hired. I knew of Paul, and, you know, that’s the first question. Okay, I‘m B camera, but who’s A camera? I found out it was Paul and then immediately there was a comfort from knowing that I’m working with solid people.

Paul Sanchez: It was pretty much the same for me. I knew Sarah as well, and her husband, who’s a camera assistant. Sean Porter was somebody I didn’t know. I had seen his films—20th Century Women, Green Room, Green Book—but I’d never met him before. I had heard he was based out of New York, and that he didn’t really have a West Coast crew and he was looking for people, so it was really a cold call. I met him at a coffee shop, and we hit it off. It was sort of a blind date, which it often works out that way. It was a new show, so no one really knew what it was. I had worked with Jeff Bridges maybe 20 years ago on a movie called Masked and Anonymous, but hadn’t done anything with him outside of that. I also hadn’t worked with Jon Watts, who was the director. He was in prep or really early pre-production on Spider-Man: No Way Home, but then it was put on hold. I can’t remember why. Anyway, his schedule opened up, and he was offered the pilot and a couple episodes. That’s how Jon Watts got involved. There were subsequently a number of other directors, but he was really the main director to start with.

CO: You mentioned Jeff Bridges, but there’s a great cast for the show. You’ve got Jeff Bridges, you’ve got Alia Shawkat, you’ve got John Lithgow. What was it like working with all of them on this show?

Sanchez: Couldn’t be better, really. They’re seasoned pros. I think I heard that Jeff and John had never worked together before, but boy, they really hit it off. We did a number of car sequences, particularly the chase sequence in the last episode—we did that in the Volume on the Disney lot. So, they sat in a car for a little bit as we’re tweaking this and that, and they would tell jokes to each other. We would hear this on the com-techs. Work would slow down as they would exchange jokes with each other, but they’re really pros. And John is great to work with, just a very personable guy. Jeff is prepared and always thinking. You know, he’s a producer on this too, so he often looked at playback and just wanted to make sure he had the big picture, and he was involved in it all. But he was really centered on his character and what he would be going through as a 70-year-old. So, if I ever asked Jeff to do something, to alter some physical thing because I just couldn’t move the camera in that position that quickly or that kind of thing, he would pause and say, “Let me think about how I would do that as this character, why I would do it that way.” And I appreciated that, that everything was considered that way. And we did long rehearsals in which everyone got to really figure out what it is they were doing. There’s a whole sequence where he’s cooking eggs for Amy Brenneman, and that sequence is actually quite complicated to do because of the props and the timing of everything. Once he’s finished, the eggs are done, so you had to time it all out. We tried to shoot it all in one shot. I think there was a cut or two, but it was all done that way and then you reset and make another set of eggs every time you do a take.

Goring: This was a very rare case of being able to stop and watch what’s happening. There’ll be different sections—if it was stunts, stunts would be working their thing out on their own, and then with the double, and then with Jeff. So, there was a lot of time for observation, which helped us prepare for the scene. There wasn’t really much you didn’t see prior, especially with some of those oners. It took everyone.

Sanchez: That’s a good point. I’d say this was definitely a choreographed dance. You’re balancing all the plates and you have to perform, and it all has to come together. You drop something and it all falls apart. And because we were doing long takes, everyone had to really focus and understand each part of it. But we also moved in somewhat slow motion too. It had its own pace that I really liked. We tried not to move the camera if we didn’t think it was necessary, but then sometimes we moved it a great deal.

Jeff Bridges in THE OLD MAN

Goring: One of the only times poor Sean would come and correct me on something was if I had moved the camera too fast. He’d come over and say, “Is that old man pace?”

Sanchez: Yeah, that’s true. If Jeff left my frame, I would let him leave my frame and I would just pan slowly. We called it “The Old Man pan” and I did try not to take it personally. But I really liked that, because when you start to see it more often in the series, you realize that the character is ahead of us. He’s always ahead of us. He has a plan, he is prepared. You see it even in the beginning, where the first hitman that shows up to his house. Chase kills him, and then he leaves the frame and he goes and makes a phone call. He’s already several steps ahead. He’s been planning this the whole time. And I think that was something we conveyed through the camera work. Instead of being with the character, every time that character showed us that he was actually a little ahead of us, and we would always sort of slowly catch up to see what he was up to. That’s something I don’t think I’d done before. You do things with the camera to provoke a sense of not being sure what’s going to happen next. In this case, we have confidence in this character that whatever is going to happen next, somehow he’s got it. He’ll have it figured out because he has so much experience that he knows what his next move is. But then at the same time, he’s haunted by the decisions he’s made throughout his life. I think that was an interesting character development.

Goring: We would have to observe the aftermath of what he did as well. And it was the recovery or just getting ready, with the grunts and the groans that Jeff gave. You kinda go, all right, that’s acting. That’s what it comes down to, going back to the original question. Every day, we got a master class of actors. For the actors that had to come in, you can really see a factor of fear, but they were coming into such a pleasant environment that—John and Jeff especially—welcomed them, brought them in, and got them down to doing their job. It was really a one-off experiencing class actors like that.

CO: It’s really interesting the way you talk about all of that. Having the camera be just slightly behind the character to portray that he is one step ahead of everybody else. I think the first 10 or 15 minutes of the the first episode are really interesting, because you’re following this character who you don’t really know yet, you’re just trying to figure out what this guy’s deal is, and there’s such limited camera movement. It’s static shots or, when the camera does move, it’s along a single axis. It’s a pan or a zoom-in; it’s not multiple moves at once. And that continues up until that first flashback or dream sequence, where he finds his wife in the bathroom, and then it’s all handheld. The juxtaposition of that is so interesting.

Sanchez: Yeah, I think so too. I’m not sure yet what the subtext is in the beginning of that, but I think, just in general, what I learned about this process, particularly with Jon Watts, was that he was really loyal to this idea of not to moving the camera. It wasn’t a stylistic so much as it was a kind of performance in which you really see an interior. This is based on a book that is very plot oriented, but it is told through the inner life, through this character, Chase.

What I really liked about the still frame is that the viewer can see everything pretty clearly. I remember in school there was a quote I read: “There’s nothing more mysterious than a fact well-seen.” Once the viewer can see everything in the frame, you look for something that’s moving, because that gives you new information. So, if the actor is sitting in a seat or standing there, and there’s nothing else moving—the frame’s not moving at all—we tend to look at whatever is moving and eventually, particularly in close-up, we look at their eyes because that’s about the only thing that’s moving. We start to look and try to figure out what is going on here. As opposed to when we move the camera, adjust it slightly, the audience has to process new information. Just a little bit, subconsciously in the background. I found I didn’t really understand that even after many years of doing this. I didn’t really understand until I started to really examine the shots, especially in playback, and I found myself going, “Damn, I’m looking at their eyes. I’m not looking at anything else.” I found that enormously powerful and very effective. So, since Chase was by himself, particularly in the first episode, we really want to show what is going on in his head, even though he’s going through what appear to be pretty banal things. He’s getting ready for the day. I think maybe that’s what was very effective about it all. It’s really affected my work after that because I started to see it as a part of my craft that I didn’t really take as seriously before. How important it is not to move the camera unless you really need to, and move it on certain axis. A tracking shot or booming shot, tilt, or whatever else, there are different reasons why you do that. I find it much more effective.

To make this point, something I really saw as a metaphor happened while we were on the Volume. So, we’re surrounded by LED screens, it’s a car going down a straight road in the desert, we had a camera, a two-shot on the hood of the car, looking through the windscreen of the two actors. Then we had a big camera looking at over the driver onto the passenger’s side.

Goring: Because we just had the two overs.

John Lithgow as Harold Harper and E.J. Bonilla as Raymond Waters

Sanchez: That’s right. We rolled the first time and it’s a long take because there’s a long conversation between the two of them. They’re the exact same cameras—maybe slightly different lens, but same card size. Within 10 minutes of the shot, I noticed that B camera was starting to get a little nervous because they’re almost running out of media. And I was just like, what’s going on here? Why didn’t they have the same card? Why didn’t they reload the same time that we did? We knew it was a long take, it didn’t make sense. I had never really seen this to such a degree, but because it’s a side angle with a view of the landscape as it’s flying by, that camera had produced an enormous amount of processing. As a result, it was using far more data. And where my camera was, in a two-shot, there was not that much changing. I had almost twice as much media left over. I’d never seen that before with two cameras rolling at the same time. I’d seen some slight change, maybe a minute or two difference, but I’ve never seen that. And I realized that is exactly what we go through as viewers. It’s just so much processing that we have to deal with. We slow down, we fill up our data. I think it can be too much for the viewer. There are words being said, there are interpersonal relationships that are being established, and the camera’s moving, and all this stuff is happening and it seems quite exciting, but at the end of the scene you’re not really sure what just happened. And I think it has something to do with that. We can’t quite process this new environment. So, I use that as a metaphor for my own work. I have to be careful. If I am not adding, I’m actually loading up the viewer with information that is unnecessary.

Goring: A lot of the traditional way of operating, especially as B camera, is “okay, you’re gonna go and get the insert of that hand.” That never happened on this shoot. We’d be in one place and we might have to push in, but then the actor would come to us. So you get the story point without having to reach for it. Like Paul was saying, it was such a nice way to work because you really introduce the room. Whatever room we’re in, we were seeing it from afar. There were no establishing shots turned into scenes.

Sanchez: In the edit, I think for the most part it worked, but sometimes they got into a little bit of trouble with how to pace it up or how to change something. So, it’s a risky way of doing it, which I kind of like. In some of my experiences in the past, sometimes we will produce 14 hours of media a day for an hour episode, and we do 9 or 10 days per episode. It’s a huge amount. We have three cameras with at least two cameras rolling all the time. At that point, we’re not really filmmakers anymore. We’re just content capturers. I don’t get to make choices like “will this cut?” or “this would be a good shot to cut with that shot.” You can cut this 20 different ways, I have no idea. Particularly when we do these elaborate dolly shots and that kind of thing, then we see the episode and it’s just cut to pieces. It’s demoralizing more than anything, I have to say.

Goring: It’s the harshest thing.

Sanchez: So, this was really nice. Obviously there’s lots of change in streaming, all this great written content is coming, and lots of new talent. It’s become more like films, and it’s a different format in the fact that you’re telling basically an eight-hour movie. Once you’ve established certain things, a lot of these things aren’t really fully realized, not even all eight scripts. By the time you’re on script 6 or 7, you can’t change it that much because you’ve already established this thing. They haven’t finished writing by the time we start shooting it, but that’s also true—I’m sure Hilton’s had the same experience—in films. We’ll start with white pages, then by the end of the film I don’t have a single white page in my script. But especially in episodic, we’re really not sure where we’re going with this whole thing. As a result, you have to live with certain choices that we made. I find that kind of interesting, too. The limitations are actually a really good thing in any creative work.

Hilton Goring operating on THE OLD MAN

WORKING AS AN OPERATING TEAM

CO: Hilton, you were talking about this a little bit, but I wonder if you could both dig a little bit more into what the working relationship was like as a camera operating team on this show?

Goring: It was good. Paul did carry the weight, and it was a new experience having to be so patient and then also in tune, because I’d get caught with my pants down if I wasn’t paying attention. We’d do this whole big setup and I’d be involved at the very beginning, and then the scene would go through and it’d be mainly either Ronin or a oner, but then B would have to come in at the end to pick up certain things or get coverage. So, it was important to have a good relationship with your A camera because you’d have to download information because Paul’s so buried in everything that I couldn’t even sometimes approach to get the little tip. But lucky enough, Paul’s such a generous human that he would come and give me a tip. “Oh, watch out for this” or “when you come in, this is going to happen so be aware.” So it was it was lovely.

Sanchez: Most of the time, it’s not A camera and B camera, it’s just another camera. And I really feel that is necessary—there are these opportunities that another camera can use when I can’t be there at the same time. It also allows the actor to not have to repeat a scene over and over again, and we only have so much time with the resources that we have that it’s important to grab as much as we can. That also helps for the cut, so the continuity is there as well. But in this case, I would say, yeah, Hilton was at a disadvantage for being there for every take. So it was important, I thought, to communicate “this is what I learned in doing these takes.” I just wanted to help to make sure that he had the best opportunity, because it might be just a few takes for him to do what he needed to do.

Goring: Sometimes I’d have to take over. You would step out, and then I’d be left there.

Sanchez: That’s right. Exactly. So, you don’t have the benefit of actually seeing it over and over again. It’s a little bit like seeing a rehearsal just once, and they say, “okay, let’s set this up.” I’m like, “okay, there are eight people in the room and we just saw it once.” So, we didn’t have the benefit of working it out. But the relationship between the jobs is very similar and they’re actually quite different. I’ve done both, and when A camera sets up, it tends to be the focus of the director or the director of photography to begin with. And B camera needs to understand, let them figure this out before we move in. Because a lot of times, we set up A camera’s 30 feet of Dolly track, but B camera is not on a dolly, and they move to try to find a shot. When I set up my shot it turns out B camera’s in it, which causes this sort of frustration of “well, I found the shot, can you just shorten your move.” Let’s work this out together. Like, let’s set up the A camera, let’s see what it is, then we bring in B camera to see, we hope, if it will work all at the same time. I might have to do something a little different to make it work, but that’s fine. I think that works well. Or we find we just can’t roll two cameras at once, so B camera’s ready for a leapfrog situation where we roll a couple of takes of A camera, done, boom, B camera goes in.

Sean Porter was particularly interested in using mostly one camera, that’s really where it came from. Also Sean, I think, is used to using one camera and operating his own camera, so this was kind of a departure for him to rely on operators, but he really liked it! It allowed him the freedom to explore more in lighting. I really think the world of him. He’s a really talented director of photography who also is just a great human being and a real great engineer of human problem-solving. He built his own house and he’s got chickens and dogs. I don’t know how he does it all. He has this enormous amount of energy to do all this. He brought in a very experienced crew, and he’s relatively young. Typically that might be intimidating, but for him it was like a great resource of information in that he would often ask us what we would do in this situation, what tools would we suggest to use, those kinds of things. If they had a shot that they talked about in prep that they weren’t really sure how to pull off, he would ask, he would call, he would text or email or whatever and discuss these things if we weren’t on set. And that’s great, as opposed to walking on set and going “oh, this is that shot” and they’ve already decided on the tools. It would have been helpful if they had asked us because we had done these shots before and now we’re struggling with the wrong tool to make it work, but Sean has a good sense about it. At least that was my experience. And it has been my experience with him since then as well.

Jeff Bridges with Amy Brenneman as Zoe McDonald in THE OLD MAN

Goring: Yeah, I think he’d get involved in setting up a frame in stills so we would always have a good reference to start from, to know what’s going on in his head at least. But then he’d hand it off to you and say, “This is roughly what I want, here we go.”

Sanchez: Yeah, what he’s referring to is that Sean uses a camera—actually the Sony FX3, it’s the same size sensor as the LF. So, he would use a still camera, and in rehearsal, he would just snap away and try different things. Then he would work with us and the director, he’d thumb through all these shots so you would get the idea of what this scene would look like, but it wasn’t camera moves or anything super specific. It was nice because it gave us all sort of a blueprint to work from for where we were going, but it allowed us to embellish and add our ideas to it as well. And then the tools: We used the Ronin remote head and a Miniscope. We used the Technocrane a lot as well, but we were always on some sort of crane where we can do slight push-ins, we can boom up and down, we can be low or high. It was really a great tool for being flexible and making creative decisions in improving on these initial ideas. As opposed to laying just enough dance floor or having just enough track—are we low enough, are we high enough—that comes with working on more conventional tools like dollies. Which I’m not against, but this was pretty great.

And then COVID happens, and when we eventually came back it was imperative that we’re more remote—that we don’t have that much contact with the actors, at least not in the same personal space. I had always hoped to someday work mostly with a remote head, but I had never really done that. We’d do special shots but never anything to this level. On this show, though, up to the point of shutting down, we’d done almost 90% on remote head, and once we came back we were doing even more remote head work. The downside is your relationship with the actors is a little more, well, remote. But the upside is that I’m right next to the director and the director of photography. We’re all lined up, Hilton and myself, and we’re in earshot of what was discussed and what was necessary, what were the concerns and all those kinds of things, as opposed to that being translated to you after the fact.

CO: I wanted to circle back to something you talked about earlier. You mentioned that the car chase sequence from the finale episode was on the StageCraft Volume. That’s such an interesting new technology with both its own advantages and challenges that come along with it. Had you ever done any shooting in the Volume before and can you tell me a little bit about what that experience was like?

Sanchez: Yeah, I hadn’t really done anything up to that point. It was pretty new technology but it’s also kind of a continuum of technology, right? We go from rear-screen projection to this, which is also rear-screen projection in a way. This was not the virtual environments that we eventually moved onto on this last project, which is another show for Star Wars. Now we’re on a much bigger Volume that is real-time rendering with our cameras, which wasn’t the case with The Old Man. We used it more for rear-screen projection, playback of plates, than anything else, but it allowed us to light and to have a controlled environment in which we could put a camera almost anywhere and shoot it as if we’re on an insert car. Which we also did, by the way! That sequence you’re talking about, we used every tool. We had a biscuit, which is basically a car that’s being driven by another individual in a seat so that the actors look like they’re steering, but we’re actually turning. It’s used in stunts. So, we used that, we had an insert car with a crane, we had the pursuit arm, we had drone, and then we had the Volume to do all the interior stuff and we married the two. We had to do a sequence in which he’s shooting out the window at all of these SUVs that are pursuing them and he shoots a tire out, which causes this entire accident behind them. I did a shot where we had an insert car with a crane—he’s shooting, the stunt actually happens—but he gets back in the car, and I go with him back in the car over to the windscreen and push in to see this vehicle behind him tumble. That part of it was an A/B part. The A part is actually on a road in the desert in Lancaster with his double. Once he goes in, we crossed the A pillar, and that A pillar was the match cut that we used in the Volume. And we did the playback because we shot a plate of that accident happening at the same time. It was ambitious.

Watch a Video About the Making of This Sequence

Jeff Bridges as Dan Chase and John Lithgow as Harold Harper

Goring: I think we started real small with the Volume as well. Remember, at the very first we were just doing little pickups with Jeff as a kind of taster. We had all the different screens that we pushed for aiming the reflections. We started on a small stage and then it grew.

Sanchez: Yeah, you’re absolutely right, Hilton. We first started with making our own sort of Volume onstage. They brought in all these enormous LED screens, and we built it and that worked out pretty well, again, for a driving sequence in the first episode. He’s driving, talking to his daughter and letting her know the game’s up, and that was all on a Volume. Then we moved to Disney for the last episode and this last thing. Then Sean and I went to Thailand to shoot a movie set in the Vietnam War and we built one for helicopter sequence where the CIA is torturing this Vietcong out the door of a Huey. We built that there and ran into all kinds of technical problems, but we managed to get by. Then the next time we worked on a Volume was the one in Manhattan Beach Studios, and it’s enormous. Every couple of weeks we were developing new techniques and new ways to make it look more realistic, so I’m really impressed. There’s a whole brain bar, you know? There must be a dozen individuals behind computers outside the stage running this thing and all the things that you have to consider. As a producer said, it’s a little bit like buying a new LED television when they first came out for $10,000, when it’ll eventually be $200 in a very short period of time. But for these VFX shots, they have to make the assets either now or later, particularly in a Star Wars situation or any situation where you would typically either be on green or blue screen. They’re going to have to add these plates later, but now you have it now.

And it’s great because the actors really are reacting to their environment. And then you also have interactive lighting that is much more accurate, so it allows us to make it feel more realistic. I feel like it’s all happening when I’m looking in the frame. Sure, it could be done in post, but it’s adding to the moment in which all of us are making decisions. Not decisions after we cut, but making decisions while we’re rolling. Everyone’s doing that to make the shot work and making it appropriate for the scene, what’s happening. I guess that’s true with any filming. We have all these plans, but once we start shooting, they’ve never worn those clothes before, they’ve never been in that room before, and they’re supposed to have an interpersonal relationship with this person. It all starts as a concept, but then we are in the room together and all of us are trying to make it work. So, by doing that, we all make these unconscious decisions to try to make it work, because we’re all there to sort of problem-solve and to achieve something that we want. I think that’s why it works. That’s why you need rehearsals, and that’s why you need to learn what’s really going on. Otherwise, I think you tend to make something based on your training. I don’t know if you’d agree with that, Hilton, but I find that’s one thing Sean is really good at. Sean has some inner sense of what he thinks he wants to feel, what he thinks the scene needs, or that story is about, and he doesn’t rely on his training. This is what we teach in school all the time. You have an idea, you want to be loyal to certain ideas, you do have to do a certain level of prep, but once you’re there and all that comes together, then you really have to react to what you’re looking at. And you have to make those adjustments and not say “oh, we need a master, and then we need the medium shot, and we need a close-up.” Yes, but more than that, I think if you don’t have a good sense of a real interior idea of what the story is about and what you want to see, you tend to lean on your training. And that’s why we keep producing the same kind of stuff over and over.

Goring: Yeah, we’re having to improvise constantly.

Sanchez: Yeah, I guess it’s improvising, but you have to have enough knowledge about what works and what doesn’t work. I think you can be very discriminating with your improvising. It’s not like we’re just going to try whatever sticks on the wall. It’s not a big experiment.

I read the book before I did the show. Big mistake. I was constantly confused by what it should be. That was where I did too much research and that really got in the way of what this story is about, as opposed to what the book was about. They’re related, but they’re different. So, I got kind of confused by that. Sometimes I think too much prep, too much knowledge can get in the way. I did this research on this story that took place in the Vietnam War. It was a true story, but I didn’t really have enough knowledge about what it was really like to be in the Vietnam War. So I did a lot of research—I had two weeks quarantine in Thailand, so I could really go deep. And it was very helpful, in a way, that I did all this research. I saw home movies from soldiers and stuff, and I didn’t know what I was really looking at, exactly. I remember at the end of this, I was like, “I’m not even sure what to do with all this information.” But I think once I was on set, I could sense what felt right because I had this sort of visual library of images that I had seen from soldiers that had actually taken these shots in photographs and Super 8 movies during the war. I think that kind of stuff is very helpful in making decisions. I always say, if you see something, say something, and I do. If it doesn’t make sense what the actor’s saying, or it seems the wrong, something doesn’t quite feel right, I’ll always question. And sometimes I’ll question not that I know something more, I’m just unclear. “This doesn’t seem like it’s very clear to me, can you make it clear to me?” And they do. Or sometimes they can’t.

Goring: Or it sparks a conversation that goes off to the side.

E.J. Bonilla and John Lithgow as Harold Harper

Sanchez: Definitely. I mean, listen, I don’t say everything. I gotta read the room, you know? There are times when the suggestion box is full. I’m not gonna make a suggestion. This works, it’s fine. They’re the director, they had this vision, and it may not be the way I would approach it, but this seems, certainly, to work. But there are times that you’ve got the three minutes while you’re building the shot where you have the moment to ask these questions. And I think, for the most part, most directors appreciate that. Danny Boyle said, “I surround myself with filmmakers. They may be script supervisors and electricians and dolly grips and camera operators, and I’m just the guy that likes to get up in the morning and tell people what to do. But they’re all filmmakers just like myself, and I depend on that.” And I think it’s really true, so I do the same. I really encouraged my crew and the people I’m working with to say something, to be involved in being filmmakers. The sets can be filled with very specialized craftspeople, but most importantly they all need to be filmmakers too. I think they’re the most helpful when that happens.

Goring: That’s so true, because I think then you’ve got a sense of ownership, as well, to the project.

Sanchez: I think it’s important in the leadership to make sure that people are involved, because it’s amazing where something—an idea or improvement—comes from. I’m always surprised. There are just so many things going on at one time, there’s no way one director can see it all. I think it’s important that when you see something that can be improved, you go make an improvement. If the director seems to want to be involved in every decision, then go ahead and ask them. “Listen, I see this. Can I change that?” But you can’t assume that the director’s watching these monitors—particularly with two cameras—and seeing everything. So, if you see something and they haven’t said anything, you assume that it must be fine, but that is not true. That’s not true at all. Sometimes I’ll say, “Oh, I saw something there.” And a camera assistant does the same thing. “Oh, did you see that? Did you see you clipped that stand?” I did not see it, so then I look at playback. Damn, I did clip it. So, it’s really important that we all say something and that we’re included. But we’re not trying to slow down the process. Sometimes it just doesn’t matter. Sometimes it does matter, but it doesn’t always matter. But it’s great that we have all these eyes on this kind of thing, because it’s all made up. The entire thing is an artifice and it’s so easy to get it wrong. So many things have to go right for a movie to be good, it’s incredible. That’s why so many movies aren’t good. They have potential to be good, but they’re not because of the 47 things that have to go right, only 44 went right.

CAMERA OPERATOR OF THE YEAR AWARDS

CO: As we’re having this conversation, it’s a few weeks after the Society of Camera Operators Lifetime Achievement Awards, where you two were nominated for Camera Operator of the Year in Television. Can you tell me a little bit about your reactions to getting that nomination?

Goring: Shock. Surprise, more than anything, because of the duration of the show. We started in October 2019, so, you know, you shelve that information in the back of your head. But I found out through a text from a camera assistant, so my reaction was, “Whoa! I can’t believe it!” What about you, Paul?

Sanchez: Yeah, I got an email from someone at the SOC saying that I was up for a nomination. My first response was, how did this happen? I didn’t submit anything. And I have to be honest, I don’t know how they make these decisions. We were part of a group of people where I don’t know how you’d make a decision that one’s better than the other. It’s really great work, so just getting the nomination, honestly, was the best part of it all.

Goring: Yeah.

Sanchez: Out of all the scripted shows, which I have no idea how many there are at this point, it’s very nice to be selected. I have to say, I’m not proud of all my work, but the work we did on The Old Man, what everyone did, I think it’s a really good show, and I really stand behind it. It was nice to see that someone else thought so too, because that’s not always the case. Often times I’ve done things that I think are really good, and they’re completely ignored. Not my own work, just the show in general. So, this was nice to see that maybe it’s of its time. And it’s nice to go to a party and see a lot of people you haven’t seen in a while. Hilton and I have been at this for a while, and I’ve never been nominated before. I don’t really take part in these kinds of things. I like making films a great deal, but I’m a reluctant participant in the marketplace of Hollywood. It’s not as bad as I thought it was when I first started, and there’s a lot of room for lots of different people to be there—that was one thing I liked a lot—but I’m not really cut out for the marketplace. I’m not that concerned about doing the biggest show, that kind of thing.

Goring: It’s being recognized by your peers. That’s the number one thing.

John Lithgow as Harold Harper in THE OLD MAN

Sanchez: Yeah. I didn’t go into this thinking that I’m really good at operating, I’m going to be a good operator, everyone’s going to see how good I am. Most of the time I’m about to go into a project, I’m thinking, “Oh God, will I be able to pull this off?” I’m filled with insecurity all the time about my abilities. My career is based on hard work and trying to ask the right questions and learn, but it’s also an enormous amount of luck and lots of people that have helped me along the way. All the good things that have happened to me are certainly other people giving me a shot. I’m always surprised. I want to fail better next time is pretty much how I see it. And I’m not trying to have this false modesty. Sure, I think Hilton and I are probably as good as a number of people. I think the emphasis so often is on the technical, you know, turning the wheels and how do you do this specific thing? That is so little of what we do. It is a little frustrating to me when I see so much focus on the technical aspects. Even the SOC has these educational programs—which are great! I think the SOC is doing a great job with that!—but they have these these weekend seminars to help people try out all these tools, the crane and the dolly and this and that, and there’s so much more to it than that. Hilton is a Steadicam operator, and it’s a little bit like learning how to use the Steadicam and saying, “Now I know how I can get the shot really steady.” That’s not operating. That’s just keeping it steady. Operating is problem solving. What do you do to make the shot work? What things need to be changed? Do you change the actors, do you change the Volume, do you change the dolly movement? What do you change?

Goring: It’s reacting to that feedback.

Sanchez: Yeah, and understanding what it is that this shot is supposed to do. Communicating with the director and the actors and all those things. It’s a little bit like football, which is something I don’t know anything about, but you see this amazing pass from the quarterback, and everybody says, “Wow, look at that pass! It was amazing! He sent it right to the tight end who catches this thing.” There are so many other things that had to happen before that pass, but all we talk about is that he saw that opening and threw it. No! There was a play made, there were choices made, there was training, the guy had to be there at the right time, he had to get through all that defense to get there, all this shit had to happen before that pass. And that’s generally not really seen. That’s sort of how I feel about what we do. I’m not trying to make it more important, but I do think it’s really important if you want to be an operator and do these things, there are an enormous amount of other factors that need to happen before you’re actually spinning the wheels. Keeping the head in the frame is the least of your problems.

Goring: I think as well there’s the importance of a good camera department, because you need that support from the ACs, from the DIT, et cetera. There’s an emotional support you need from a good department. If all those things aren’t in place, if someone’s bickering with someone or there’s just something off balance, it throws everything off. It’s about energy, right? We have a great energy within everyone’s separate personalities, and that energy enables you to do your job. And that job, like Paul said, is made out of 5 million categories. Some lead some days more than others, but you need everything to be balanced. Once it’s balanced, you’re in a good position.

Sanchez: And that’s why crews work together over and over again. They sense that and they understand they have some differences—we still do—but we work them out. There’s a certain kinship to why we’re doing what we’re doing, and we see that we have a similar worldview of it all, and I think that’s very helpful. Directors recognize that and actors see it, too. It’s just supporting each other and definitely recognizing that when there’s some great work, they need to be recognized as opposed to not saying anything if there’s not a problem. That’s just poor management when you are not encouraging others. At this point, camera assistants will come to Hilton and I asking “how do you do this?” Or there might be some political problems and they’ll ask us how they should handle these kinds of things, and I’m really glad that we have that experience to help the next generation when they come to us and ask. They want to do what I’m doing, and I’m happy to help.

And that’s what this discussion is about right now. It’s an opportunity to at least emphasize what you think is important to succeed and what this job is about. We all have certain temperaments, and it’s about figuring out whether your temperament will work within the skills and the demands of this particular job. When I first started out I was a loader, and then when I became a focus puller, on my first couple of jobs I thought, I’m just not very good at this. But I don’t have to be very good at everything. It was one of those things where this seemed just impossible, but I kept at it, and eventually I made a living at it. I was always surprised by that kind of thing, but it’s also because people helped me. I saw tools and I saw people figuring these shots out and they were enormously helpful to me. There’s a lot to be said about asking other people “how do you do that?” But doing it is certainly what it’s all about, and you find your own techniques. I have to employ those techniques, particularly when I’m actually in the midst of a shot, how do I create a certain level of focus? I have techniques to do that. It used to be that I was annoyed, like any operator would be, if there was somebody leaning on your cart or your camera, or they’re talking or something’s moving. And I would say, I can’t concentrate. Now, I welcome it, because it’s part of my training. Because that’s what happens. If I lose the shot because someone’s eating potato chips behind me, I just can’t do that. It’s annoying, but I don’t care. And they sometimes apologize, but it’s fine, and I never had that perspective before. But I realize you have to find a way to concentrate and focus. And when you do, the job becomes easier. But if you don’t have that, it seems impossible. How am I going to do this with all these things happening at one time?

Hilton Goring operating on THE OLD MAN

Goring: Yeah, that really is important to have that tunnel vision, to block out everything else, because you’re just waiting for that moment of “roll camera.”

Sanchez: Yeah, exactly. “Quiet on the set.” And I’m worried about, “well, I don’t want to clip that light again, I don’t want to do this, I have to remember this is going to be tricky here,” but once you’re in it, I just look for something on the screen—often it’s the actor—and I really concentrate on that thing. And I tell you sometimes, it’s silly, but there are times when you’re in the middle of night, you’re ready, you’re setting up, and I can’t remember which way to turn the wheels if I thought about it. But then I hear, “action,” and all of a sudden, it just happens.

CO: Yeah, that muscle memory.

Sanchez: But if they asked me which way you’re supposed to turn the wheel, I can’t remember. And I panic a little bit, just for a moment, because I know I’m not focused on what I’m supposed to do. I’m anxious about something in the shot. Then I go, “Okay, the first thing I’ve got to do is tilt up. Aw shit, which way is up?” But if I’m focusing on this person and I see him stand up, boom, it happens.

Goring: Or the actor does something different. Suddenly the actor just ran out the door. And you’re like, “that was new,” but you got it.

Sanchez: Because you were concentrating. Sometimes my best takes are the first take, because I’m learning, I’m watching, as opposed to overthinking it after many takes. But I still surprise myself to this day that if I overthink it, I don’t know how to do it.

One thing we didn’t talk about is some of the shots that look like oners, but they weren’t. They were very orchestrated and designed to match cut. That was a tricky thing, particularly the fight sequence in Episode 1 in which he takes out these guys that are looking for him. There’s a whole fight sequence that happens on this dirt road, and we did it all on a 30-foot crane, but we did it over three nights. Each shot had to be frame accurate, so I’d actually take a frame grab from the end of the shot on the previous night, and then I then I would double expose it on my monitor and frame it for the continuation of that shot. I had be very accurate, and I’d say “set,” and we would continue the action. That was very labor intensive. Then they would take the playback and edit right on set and see if we got a good cut in that. And the effects supervisor eventually sort of massaged it a little bit more in post, but he said it was really successful because of how we did it that way on set. We had to really figure out how long to continue that shot. Part of it was due to the fact that Jeff couldn’t do all those stunts, so we had to intercut with a double of him, so figuring out when would we do that and how would we do that. That was something I had done to some extent, but never to the level of that whole sequence—it’s over four-and-a-half minutes long. It’s also kind of an unusual way of doing a fight sequence that I liked. That was fun to do, but it did take specific prepping and tools. We worked out this fight sequence with cardboard cars and a smaller crane on the stage floor. We worked it out with stunt people, not with Jeff, as a proof of concept. Would this work, how would we do this, what kind of size crane, and then we scaled it up. I liked that idea. The idea is certain things that you want to try and you’re not sure how to put this all together, it’s really important to have a moment in which you can do that proof of concept. What did we learn from this and what tools do we need to do it, as opposed to using all these resources and bring everybody in and realizing this is not working. If you can push for that, I think that’s really important. As an operator, it’s really helpful for you to be part of the decisions that are being made. You’re then more prepared for what you need to think about.

Goring: Yeah, you’re not just being told. And Chris, your dolly grip, he played a part in operating as well.

Bill Heck as young Dan Chase in THE OLD MAN

Sanchez: Yeah, definitely. The dolly grip, Chris Thrasher, operated the crane as well as the dolly, and Chris was a big part of the success of this whole thing. He’s a filmmaker too, he’s a huge film buff, so with our shorthand we could talk about certain things and certain films and he could sense that this is what that shot is about, as opposed to just going from mark to mark. So when I’d say, it’s got to be a little slower, more this or more that, this is more of a Spielberg push-in, he understood what I was talking about. “Listen to the music.” There’s no music on the set, we’re just using terms that help us remember we’re making a movie, not just a technical thing where you told me just to go from here to here. And he could see things from his perspective on set that I couldn’t while I was often just off set with my monitor and the wheels. He had a good sense of “yeah, I saw this, and I had to make an adjustment.” And I was unaware of that, because I’m only seeing what my camera sees. Chris is a big part of it. I’ve always felt that way.

Goring: It was cool to see from my point of view as well. Sometimes from the B world, I’m seeing the A world over there, and it is a dance. And especially what you said, Paul—being on set and having to operate from a distance, your communication with Chris was essential and it showed in the picture.

Sanchez: And while we’re shooting, I can talk to him with our intercom system and let him know, slowly push in now. Go, go, go, go go, stop! That was very helpful that we could see an opportunity and take advantage of it, and he wouldn’t say “we didn’t plan that.” He had his finger on the pickle, and he was ready. And he knew not to move the camera on a line. There’s a lot that comes from experience, and it comes from also knowing what I like and don’t like. There are times when I don’t really know what I’m doing and I get 80% of the idea, we set the shot up and the dolly grip has to be quite patient about how we’re figuring this out. “Go a little higher. No, go lower.” I’m fishing. I’m trying to figure out what it is that this should be. I don’t always know, and none of us do. That would be true with everyone on set. When someone says, “I like to work with directors who know exactly what they want,” that’s impossible. I just don’t think it exists. If they do, that’s just arrogance, and they’re going to run into a problem.

Goring: One of the plusses that came out of this show for me personally, especially standing by with B camera at the time, I had the most incredible conversations with John Lithgow about football. He’s a huge fan. Then there was one story when I got called into set, the ADs called me in and said, “John needs you on set, you need to get on set.” So, I ran on set, I went over to John, and John went, “Did you see that game on Saturday?” Again, that just shows the brilliance of him because usually you don’t want to talk to an actor before they’re in their scene, but he would force me to talk to him, and then jump straight into a five-minute scene and not miss a beat.

Sanchez: I’m about to go do Season 2 next week, so I’m really looking forward to working with John and Jeff again and learning more jokes from them. We have a good time. And the producers are really great. That’s the thing about it all, it’s really unique, and I just think the world of everybody on it.

Camera Operator Spring 2023

Above Photo: Jeff Bridges as Dan Chase in THE OLD MAN

Studio stills by Prashant Gupta/FX. BTS photos by Byron Cohen/FX.

TECH ON SET

ARRI ALEXA Mini LF

ARRI Master Anamorphic Lenses

Chapman Dolly

Chapman Miniscope

Scorpio 30’ Technocrane

DJI Ronin 2 Remote Head/Gimbal

BEHIND THE SCENES

Select Photo for Slideshow

Paul Sanchez

In 1984, Paul Sanchez left the small seaside town of Santa Cruz to pursue photography at the San Francisco Art Institute. Ten years later, after studying painting, music and experimental film, he then found himself working as a 2nd assistant on the set of Mrs. Doubtfire. This was the beginning a 30-year career in film and television that has included operating on Sideways, 3:10 to Yuma, Walk the Line, Mad Men, The Old Man, and most recently, Star Wars: Skeleton Crew. In addition he has made many award-winning documentaries with his wife, Mary Trunk, over the past 35 years.

Hilton Goring

Born in London of Guyanese descent, Hilton Goring has worked in Hollywood for over 25 years starting as a camera loader and 1st AC, then entering the world of operating via Steadicam. Hilton’s craft as an operator grew under the tutelage of some of the world’s top directors and cinematographers. This, combined with having the good fortune of collaborating with some of Hollywood’s finest ACs, operators, and technicians, has allowed his career to flourish. After working in the world of commercials and sports promos, next came feature films and television, where Hilton’s abilities as a versatile operator have taken him to many continents and created great friendships and experiences. Hilton resides in Los Angeles with his wife, two daughters, and cat and supports Tottenham Hotspur FC.

David Daut

A writer and critic for more than a decade, David Daut specializes in analysis of genre cinema and immersive media. In addition to his work for Camera Operator and other publications, David is also the co-creator of Hollow Medium, a “recovered audio” ghost story podcast. David studied at the USC School of Cinematic Arts and works as a freelance writer based out of Orange County, California.