THE SHAPE OF WATER: The Art of del Toro

Above Photo: Sally Hawkins and Doug Jones on the set of THE SHAPE OF WATER. Photo by Kerry Hayes. © 2017 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation All Rights Reserved

By Gilles Corbeil, SOC

Director and writer, Guillermo del Toro helms this other-worldly fairy tale, set against the backdrop of Cold War era America circa 1962. Co-written with Vanessa Taylor, the story unfolds in a hidden high-security government laboratory where she works, lonely Elisa (Sally Hawkins) is trapped in a life of isolation. Elisa’s life is changed forever when she and co-worker Zelda (Octavia Spencer) discover a secret classified experiment.

Looking back at the process of making The Shape of Water, and then the final result, I have to take stock of my good fortune. I started my collaboration with director, Guillermo del Toro, and DP, Dan Laustsen in 1996 on Mimic. A shoot where taped pant legs to prevent cockroaches from entering, while floating a Steadicam over subway rails, was the norm. I only had four year’s of experience with a Steadicam at that point, and it was a big break. Guillermo impressed me with his creation of a world where it was plausible to have a 6’5”cockroach. The level of detail was everywhere and the world he created was a filmmaker’s playground, and his passion for the subject matter made you want to do good by him. He was patient with the crew. Dan Laustsen would say, “Super cool!“ and was always sympathetic. The set was so dark I would often have no image on my old 3A sled. The sometimes slow-moving camera, like a cheetah stalking prey, wrapping around actors close and wide in sync. I had to learn how to walk super slow on Steadicam, and match moves.

Sixteen years passed and Guillermo came back with Pacific Rim. He did not forget his team. We all had developed as filmmakers and were ready to tackle a $190 million budget. One of my favorite sets was the 80’ trawler in high seas, captured by two 50’ technos dodging heaving hulls and pounding water cannons.

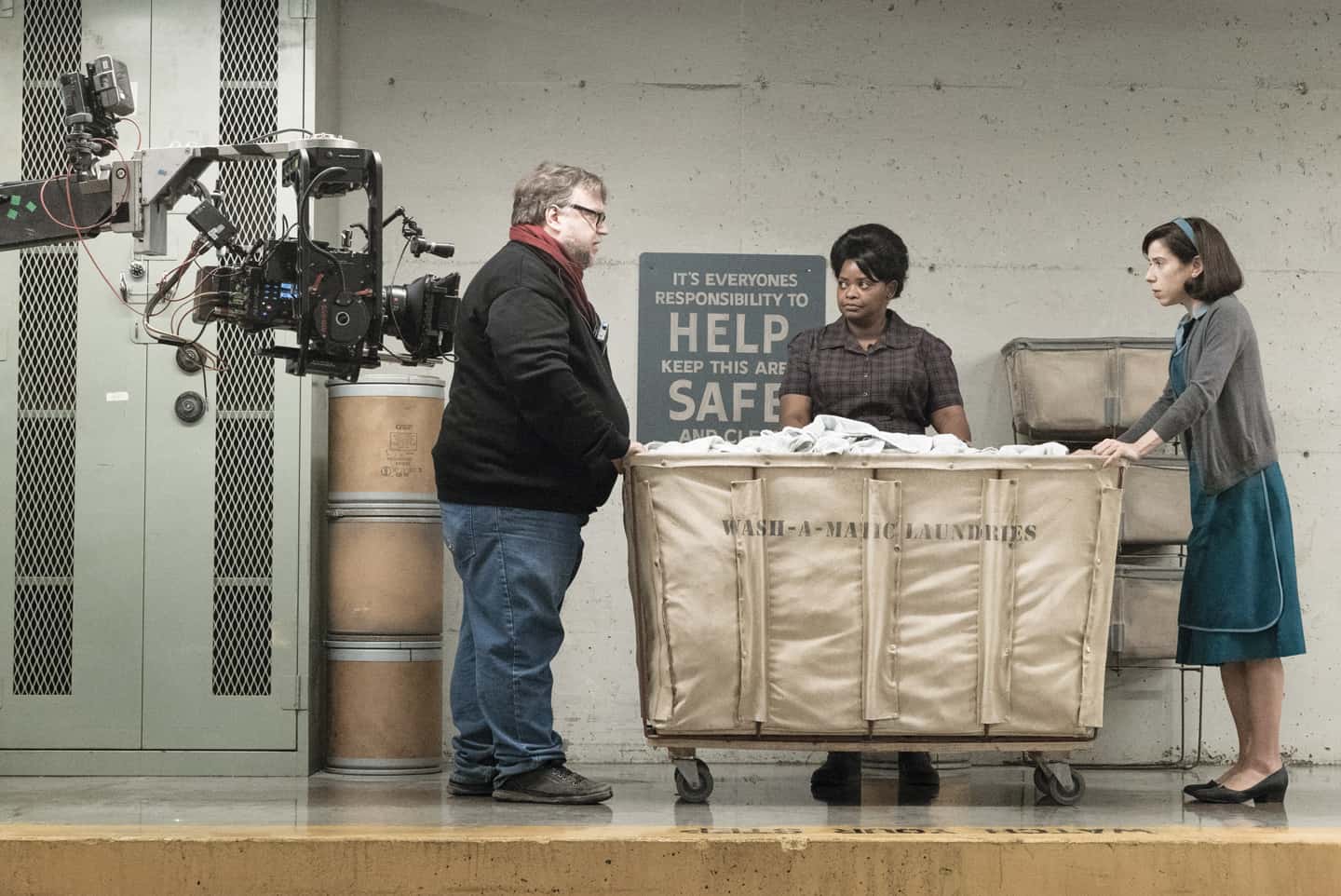

Gilles Corbeil, SOC on the set of The Shape of Water. Photos by Kerry Hayes

CUSTOM-MADE ELEVATOR

Crimson Peak, with intense performances and sets beyond belief, was a visual feast. Guillermo had the set built with an elevator that would adapt, with expansion inserts on three floors to allow me to ride with the Steadicam outside the cage. Both Pacific Rim and Crimson Peak, relied heavily on Steadicam.

On Pacific Rim I think I did two dolly shots, and lost 14 pounds in the first month.

SMALL BUDGETS ARE HARD WORK

The Shape of Water was a challenge to do on a $19.5 million budget. The sets were recrafted from The Strain. We started with a 50-day schedule. There were time limits when working with actor, Doug Jones in the fish suit, and we used every inch of the set in almost every shot. About 70 percent of the film was shot on an Aero crane with a Mo-Sys L40 head on dance floor, the rest on Steadicam or telescoping crane.

(From L-R) Director/Writer/Producer Guillermo del Toro, Octavia Spencer and Sally Hawkins, on the set of THE SHAPE OF WATER. Photo by Sophie Giraud

MOVING THE CAMERA

The camera in The Shape of Water floats. The film language is about flow and continuance of camera motion. I would say the roving camera is a principal character in Guillermo films because the viewer is constantly absorbing the evolving environment, and the path of the camera stitches together moments and a story. That environment resonates with the characters and the story, and the camera is always in a very special place, guided by Guillermo with confidence and wisdom. Some directors move the camera on a straight track in often arbitrary and random selection of lenses, or master, medium, and or close-up coverage.

Under the guidance of Guillermo he makes it easy to connect the dots with dialogue specific, or posture specific, cues. The actors and story motivate, and give reason for cradling the moments. The moves are always calculated and remind me of Jacques Cousteau footage but combined with intimate moments or tension-filled standoffs. With Guillermo, the process of plotting out a shot is done in a methodical manner. Two or three rehearsals to set the pace. Dan Laustsen was always adapting placement of lights to suit evolving angles. Guillermo likes a quiet set and adjusts one or two variables per take. He relies on the camera to replicate moves exactly, and he sets up shots like a Swiss watch.

Sally Hawkins and Doug Jones in the film THE SHAPE OF WATER. Photo Courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures

PLOTTING SHOTS

We were blessed with actors that shared the stage with the camera, so we didn’t need to explain what we were doing. Guillermo’s directions are always entertaining, and if you can imagine him explaining a shot to you, and you get to handle the camera for him, it’s like looking into the movie theater and seeing the mise-en-scène.

On most scenes, we would use an Aero crane with a Mo-Sys L40 remote head. We’d position the jib arm after laying dance floor, two layers of ¾” birch plywood, good on both sides with offset ¼” hard blue plastic (the kind that gives you a shock), stick the Mosys head on, grab a 21mm or 27mm, and rehearse. We would tweak and sometimes add more floor. If changes were made, Guillermo would elect what adjustments would happen. He would count on our consistency because his world depended on it. We would never just move the camera randomly and change the shot relationships with time and space.

When production started, Guillermo discovered A camera dolly grip, Ron Renzetti. He is someone special. We last worked together on Dawn of the Dead. After a couple of scenes on an Aero crane, I know Guillermo knew we could give him camera moves that would never end. I would say the roving camera is a principal character in Guillermo’s films because the viewer is constantly absorbing the evolving environment, and the path of the camera stitches moments and a story. That environment resonates with the characters and the story, and the camera is always in a very special place, guided by Guillermo with confidence and wisdom. Some directors move the camera on a straight track in often arbitrary and random selection of lenses, or master, medium, and or close-up coverage.

Richard Jenkins and Sally Hawkins. Photo Courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures

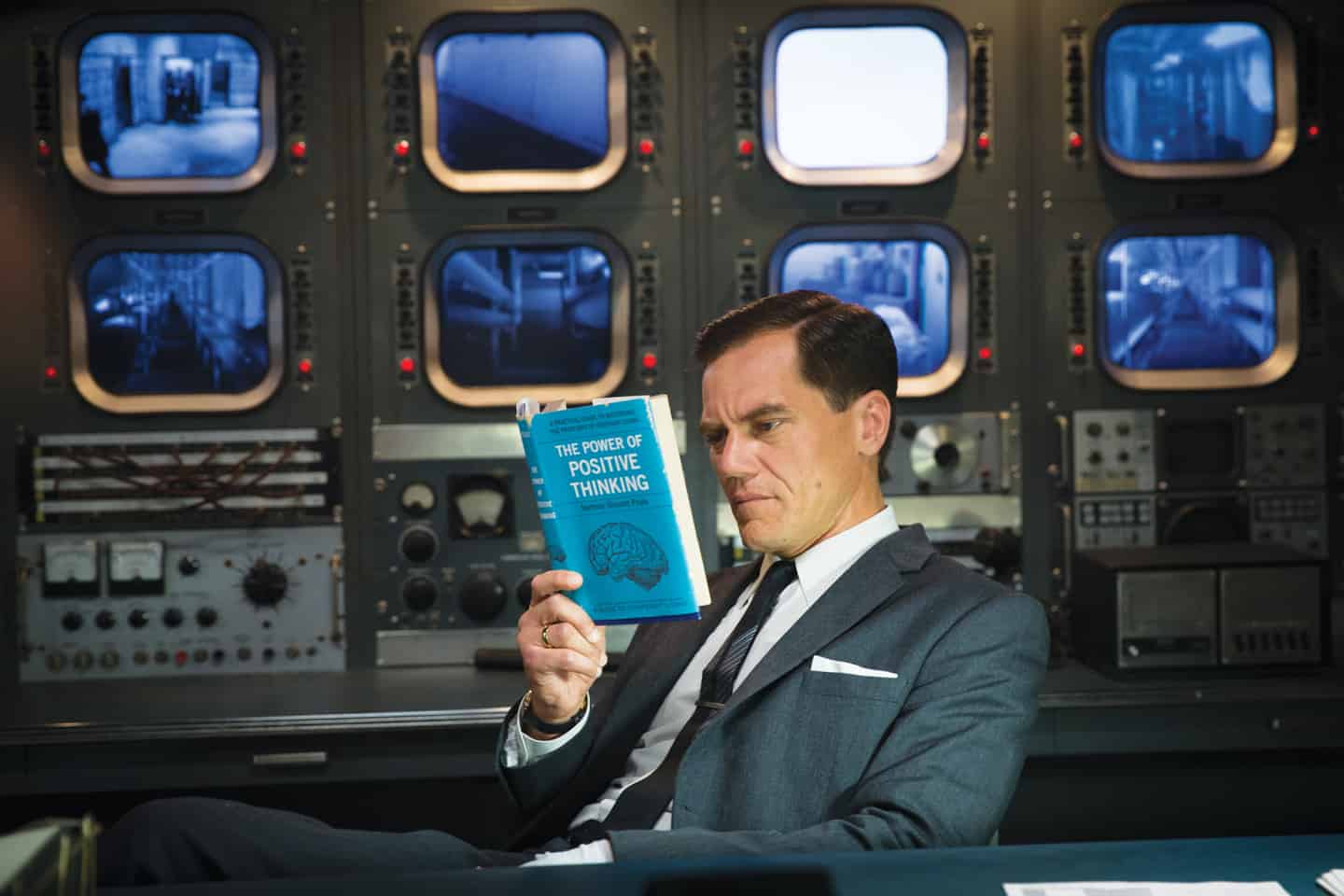

With the help of B dolly grip, Mike Yabuta we would thread a jib arm in tough sets like Strickland’s (Michael Shannon) office. Shots that look in both directions without seeing the dance floor, the camera migrating through nail biting performances across a desk, starting from across the room to, in tight on a 27mm two feet away. Our stops were around T 2 ½, and combined with the wider lenses, the texture of the set is palpable and period accurate. Depth is reinforced when you relate to it, and see it close-up.

In the scene when the creature is brought into the lab, the shifting perspective occurs by wrapping the lab set with the Steadicam on a 27mm lens which allows the viewer to ponder, “What will happen next?” Then the attention shifts to hearing noises from inside the creature’s enclosure, moving in to see together with Sally and Octavia, what is making that noise? Bang! A webbed hand slaps a portal. We’re hooked. Moving camera hooks viewers because they’re engaged and invested in a journey.

The Steadicam work was obliged to look like jib work with super slow moves (when I had to balance on one foot at a time), or tracking dead straight, center ice, in hallways. Quite a few shots, like the General versus Strickland pep talk, had to be Steadicam because of space issues and when inserted between jib arm shots, were challenging set pieces.

Photo Courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures

DRY for WET SETS

The opening shot in the film starts with an underwater Amazon river, forward-moving perspective that transitions through collapsed stone foundations guarded by waving plants, into a teal-hued hallway. When I first saw the animation transition into the Steadicam shot into Sally Hawkins’ apartment, I thought man! This is so cool! Dan Laustsen’s dry for wet lighting emulated the sun’s rays playing on floating furniture, with Sally sleeping on a sofa, her feet in the air. Shots like this are a gift and help set up the soul of the film. There were several effects people floating furniture using suspended wires on pulleys. The same technique was used for the ending with Doug and Sally.

The bathroom underwater scenes were made using the same wall segments from the set, segments made for underwater use by using automotive bondo instead of plaster and aluminum, or thin plywood. Thanks to Brent Robinson, SOC who hit the ground running, shooting underwater in a tank built on set. We always hire him for underwater work. Great guy.

Gilles Corbeil, SOC on the set of The Shape of Water. Photos by Kerry Hayes

RAIN FOR DAYS

We had about 12 days of rain, with temperatures dropping in the Fall. 1st AC, John Harper had to deal with the potential of fogging spray deflectors, and the FX dept helped warm the rain water when it was warmer, and not when ambient temps were cooler. The scene at the sand pile with Michael Shannon and Michael Stuhlbarg used about nine water trucks worth of water. November in Toronto in the rain, all night-for-days was not easy, and I still get chills when I see the footage. I have never worked harder on a film, and Guillermo and Dan always appreciated deeply the work of their crew.

After sharing more than 300 days of filmmaking with Guillermo, there is a shorthand that has developed in setting up shots, and framing moments he has created. He has become very efficient and powerful visually. By marrying the floating camera to the storytelling I think the viewer becomes more absorbed in the narrative.

MANY THANKS

I would like to thank Guillermo for his loyalty and confidence in me; DP, Dan Laustsen for giving me great advice and feedback; Robert Johnson, key grip, J.P. Locherer, B camera operator, my 1st AC, John Harper, and producer, J. Miles Dale who worked his butt off.

Gilles Corbell, SOC on the set of the shape of water. Photo by Kerry Hayes © 2017 Twentieth Century Fox Film

Corporation All Rights Reserved

Gilles Corbeil, SOC

Gilles Corbeil, SOC was born in North Bay Ontario, Canada. His first camera assignment was in third grade covering a school trip. He attended Ryerson Film School and shot docs in Europe during summer breaks. Gilles was DP on several low-budget features including The Brain. While working as 2nd AD on Rin Tin Tin: K-9 Cop, his wife, Christina Kaufmann convinced producer, Hebert Leonard to give Gilles a shot as operator.

Credits include; Dawn of The Dead, John Rambo, The Corruptor, 16 Blocks, The Recruit, The In-Laws, Hot Tub Time Machine, Spotlight,11.22.63, Umbrella Academy, and for Guillermo del Torro, Mimic, Pacific Rim, Crimson Peak, The Strain, and The Shape of Water. He holds a U.S. Patent No. US5389987A Titled: A motion translation device for positioning cameras and other aimed instruments. Photo by Christina Kaufmann

Read More Stories from Camera Operator

Print and Digital Versions Available