Ferrari

Telling the Truth

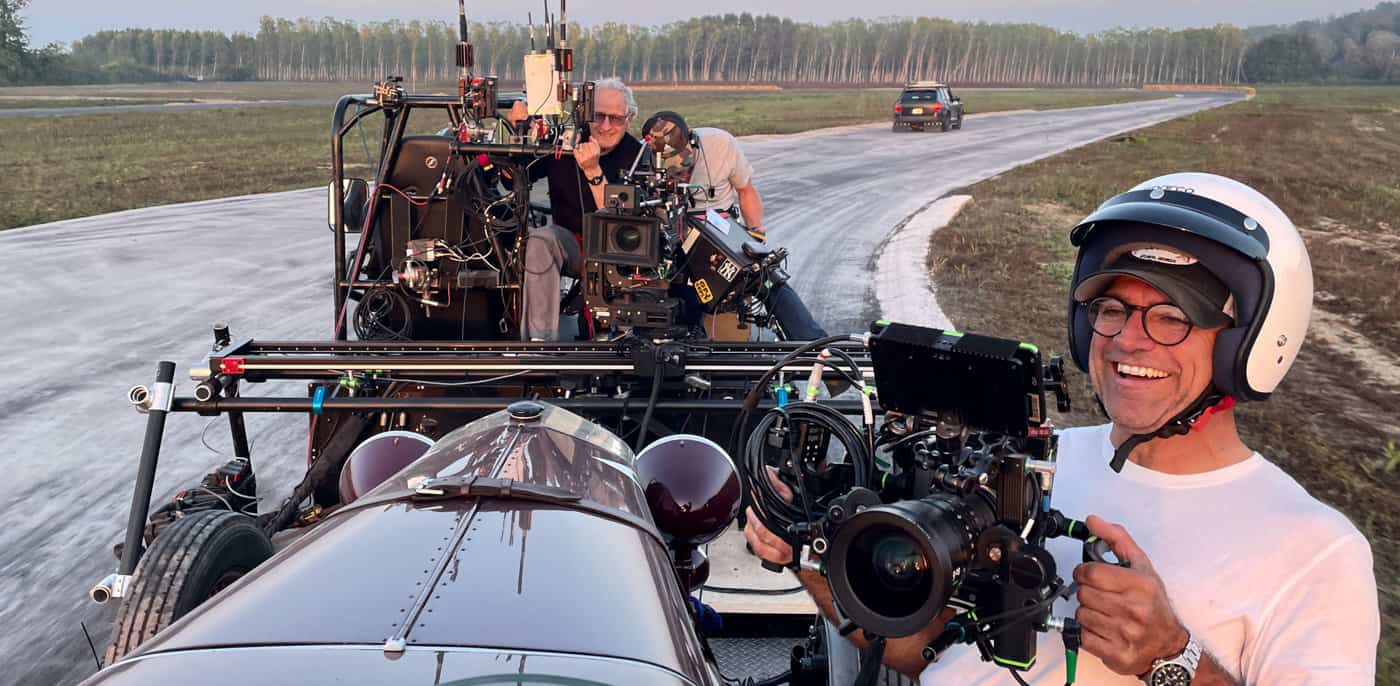

A Conversation with Roberto De Angelis, SOC

By David Daut

Eight years after 2015’s Blackhat, Michael Mann returns to the director’s seat with a film based on the life Enzo Ferrari, founder of the legendary car manufacturer that shares his name. For roughly 20 years, Mann had explored the idea of doing a film about the life of Enzo Ferrari, with the project going through several permutations and casts before finally arriving in 2023 with Adam Driver in the titular role.

Camera Operator had the opportunity to talk with A camera and Steadicam operator Roberto De Angelis, SOC, about what it was like working on this film. Whether it’s the spectacle of fast cars and violent crashes or the intimate personal drama of three people navigating a messy affair, De Angelis notes that above all, Mann’s edict for the film was one of finding the truth in these moments.

During the summer of 1957, in the lead-up to what would become the last-ever Mille Miglia race, several long-brewing conflicts in Enzo Ferrari’s life boil over into crises all at the same time: he is facing potential financial ruination for his company, the exposure of a long-term affair and a second son, and the recent death of one of his drivers on the track. Ferrari is directed by Michael Mann from a screenplay by Troy Kennedy Martin and stars Adam Driver, Penélope Cruz, and Shailene Woodley.

Camera Operator: So, as one might expect from a film called Ferrari, there’s a lot of action that involves cars. What were some of the challenges that came along with shooting in and around vehicles in this movie?

Roberto De Angelis: Before answering the question, I would like to specify one thing, Ferrari is not just a movie about race car driving. It is much more. It is a movie about love, loss, grief and challenges.

The biggest challenge shooting with the period cars was just where to put the camera. All of the cars besides the Ferrari 801 were built for the film. The 801 is the mono-seat we used when Behra breaks the track record. We had chassis and engines from Caterham Cars UK, and then we mounted the rebuilt Ferrari bodies by Campana. Campana is a very famous body shop in Modena that has been working with Ferrari and Maserati for a long time. Ferrari gave them scans of the original cars, and they rebuilt them exactly the same. The challenge for us was where to attach cameras, because there are not a lot of places you can mount them, and they’re very fragile.

Campana drilled some holes in the actual body and chassis so we could attach cameras. Michael wanted to use remote-controlled sliders. We were operating from another vehicle, and we would be able to slide the camera from the front wheel, for example, to the passenger seat, and then be able to pan left and right, so it looks like you are outside of the car, and then suddenly you are inside the car. Ultimately, though, we mostly did a lot of handheld. I was in the passenger seat and I would just put the camera outside, and then pan to the pilot or to the other cars passing by. That was the biggest thing for Michael—how to make those races feel like they’re from the pilot’s point of view. How do we make them feel real, like we’re there with them? That was really one of his focal points. In fact, before we shot Ferrari, I was on another movie in Paris, and I flew in to Modena. It was Michael, Robert Nagle—our stunt coordinator—and myself. We did some tests in a car on a circuit they use for students in racing school, and we decided that handheld was the most efficient way to shoot, and that was the way we went.

Michael and I have been talking about this movie for a long time. We met just before Public Enemy, and we’ve worked together ever since. I admire this man so much because of the way that he approaches his movies, his details are so meticulous and he always strives to tell the truth. In the two crashes you saw in the film, even if we had more spectacular shots, he would favor the truth of what really happened.

We had a lot of archival material provided by Gabriele Lalli, a historian from Ferrari, and Gianluigi Buitoni, a consultant for Michael Mann and a Ferrari expert. Our special effects supervisor, Uli Nefzer, did a lot of research on the dynamic of the infamous accident where 11 people lost their lives, and what you see in the movie is the truth. Our car ended up in a ditch in exactly the same position where they found the real car. That’s truly a miracle when you think about everything that went into creating that crash. That car started with a computer-controlled remote—no pilot inside—going more than 100 kilometers per hour. When we fired the cannon, which is a device that flips cars in motion, the car travelled in the air for 200 meters. We achieved an incredible oner, but Michael wanted to stick with the truth. In the real crash, before the car landed in the ditch, it hit a light pole on the other side of the street and then bounced back towards the ditch. That required visual effects and another shot to cut in, but I love the fact that he decided to stick with the truth instead of choosing the more spectacular shot.

The movie has been years in the making, and from the very beginning, Michael has always wanted the movie to feel very classically shot. There is a lot of Steadicam and track in this, very different from his last few movies that used a lot of handheld. We decided to use handheld only in the races. The races are meant to be really hectic, and you have this incredible sound. It’s a contrast between the drama and racing scenes. For the drama, we used a lot of Steadicam with a Skater Scope, which was a big challenge for E.J. Misisco, the first AC. For example, there’s a shot when Enzo arrives at the hotel and meets Lina during the Mille Miglia. People probably think it’s a normal shot, but it’s really not. He parks the car, goes upstairs, enters the door, and the camera is literally four inches from his face. Michael loves using the Skater Scope to really get inside of the character. It gives us the ability to go extremely close to the actor’s face, but you can understand how complicated it is for an operator not to bump into the actor and for the focus puller to keep things in focus. Many of the close-ups of the pilots while driving were done with the Skater Scope mounted on the handheld camera. There is a great close-up of de Portago just before he dies, where the camera was a foot away from his face, creating the “Micheal Mann” signature shot where the actor’s face and the surroundings are in a perfect prospective.

CO: Speaking of that scene right before de Portago’s big crash in the Mille Miglia, there’s a really cool shot that looks like a dolly zoom from his perspective inside the car, looking down the road. How did you accomplish that shot?

We were resetting the Scorpio Arm Car, and I was zooming out while our very experienced pilot, David Ambrosi, was driving very fast. Michael noticed and said “that is terrific!” We did two or three driving passes at really high speed, zooming out equally fast, and that’s how we got that shot.

We did a similar thing during the Mille Miglia race on top of the mountains on the plateau of the Altopiano di Campo Imperatore. That’s a very special place; high altitude, but super flat. The big challenge up there was the cold weather. You know, the cars don’t perform the same, and we didn’t have a lot of time. Being Italian myself, and very familiar with the geography, Michael thought it best for me to collaborate with Janice Polley, a legendary location manager. We scouted by land and also for a day by air, which was, yes, a luxury, but a necessary one. I told Janice I wanted to show her Campo Imperatore and when we flew there to show Michael, he fell in love.

In the Altopiano scenes, we used a mix of drone, Arm car, and handheld helicopter shots to match the handheld footage in the cars. All the footage with Behra and de Portago going downhill before Behra goes off the road was Arm car. That happened the last day of production, which was epic. We ended up in a helicopter, E.J. Misisco, Michael, and myself. It was barely after sunset when we did those helicopter handheld shots, and when we landed at base camp, the whole camera department was there together with other people from the crew. They brought slates, posters of Michael’s old movies, books, photographs, and Michael spent an hour signing all of it. I’ve never seen something like that in my life. It was a great ending for the movie.

E.J. Misisco put together an amazing camera department team, one that we developed over three movies in Italy, headed by our Italian key 1st AC, Andrea Quaglio, B camera focus puller, Alex Scott, and our three other camera operators, Agnieszka Szeliga, Mike Jones, and Brian Osmond. We had an awesome key grip, Giorgio Pezzotti, whom Michael loved. Giorgio was so committed and loved Michael’s work ethic—he was a good fit. Michael enjoys to be part of the camera department, and he has been calling us for his projects for years. It’s very important for him to be surrounded by people that have the same work ethic and passion, and that’s what I really admire about him.

You see that same work ethic in Adam [Driver]. Adam is very committed in his integrity as an artist. He’s really an actor’s actor, putting himself one-hundred percent into this role. He’s meticulous with all the details like Michael is, and also like Enzo was. Enzo also was a very meticulous person. Penélope [Cruz], was perfectly cast as Laura Ferrari. Like Laura she is a strong, smart, and resilient Mediterranean woman, who loved Ferrari regardless of his faults while at the same time running the company. Penelope nailed the role. Shailene Woodley gave a great performance especially considering she had little to work with as not much is known about Lina Lardi. Shailene got in touch with Piero Ferrari, who was a valuable source on Lina’s background that she used successfully.

Going back to accident scenes, the first one is when Castellotti tried to break the track record that Behra had just established. Castellotti died simply because he missed the shift between fourth and third gear. Michael really wanted to explain this well, which again is probably not the most spectacular way to show a crash, but watching the movie you understand what happened. We mounted a fixed camera so you could see what the pilot was doing. The steering wheel was going one direction, the tires were going in another direction, and one can see that he missed the shift, the car drifted, hit the curb, and flew 40 meters in the air. Uli, the SFX supervisor, had this launch tool they called “the helicopter.” It’s a catapult that winds up so that when it releases the car, it goes flipping while flying in the air.

When I was directing second unit for a French movie about 12 years ago, Uli introduced me to Falko Friesecke, an engineer who builds computer-controlled cars. If a scene calls for a car to do a jump, a computer inside the car records the previously rehearsed jump approach with the stunt driver, and a driverless car then repeats the whole stunt without the need to risk human life. We added green roll bars on the cars, which were later erased with CGI. But even so, it’s an older car, and it would be really dangerous for those pilots. Pilots at that time, they really were mavericks. If you think about it, there were no safety belts, helmets were tiny, tires were narrow, and drivers were traveling at 250, 280 kilometers per hour.

CO: I wanted to jump back to something you said earlier on, this idea of wanting to capture the truth of an event, even if it means sacrificing some of the more spectacular shots. It’s interesting, because you’ve got this contrast between the big spectacle of the races and the crashes, but then there’s this more intimate character story between these three people. Obviously you have news footage and pictures for the race and the big crash, but the more personal side is stuff that only the people involved would have known about. Can you talk about what it was like working with the actors to find the truth in those more intimate moments?

De Angelis: Michael spent hours and hours on research and talking to people, as did Adam, Penélope, and Shailene. They all really worked hard to put on screen those emotions. One never truly know what happens in a bedroom, but emotions on screen were authentic. I think, actually, that’s the best part of the movie, the relationship between those three characters. When Laura discovers Lina’s house for the first time, it’s very powerful. Penelope really delivers the emotion of a woman that’s been betrayed not just by her husband, but by the city, because everybody knew about the affair except her.

Modena is a is a small, tight-knit community where everyone cares about each other and that is what Michael loved about it. The city was obviously a part of the movie, small but with a huge history. It boasts some of the best food—Parmegiano Reggiano and balsamic vinegar, just to name a few—as well as great car manufacturers such as Ferrari and Maserati. It’s really special. For me, it was a special movie because it was in Italy, with Michael, and about Ferrari—one of the most iconic companies in the world.

This summer Michael asked Gianluigi Buitoni and me to screen the movie to most of the Ferrari crew, including Piero Ferrari, vice chairman of the company. Watching his reaction, I think Michael really nailed the movie.

CO: Yeah, and working with those performers in some of those more intimate moments. I know there’s a lot that’s been said about the relationship between the actor and the camera operator. What is it like being in those moments with those three performers?

De Angelis: Michael likes the camera really close to the actors, therefore I always try to be invisible to them. Especially with the Steadicam, you’re not looking at them, you’re looking at the monitor, so all they see is my hat. In my opinion acting is probably the most complicated job in the movie business, so I have much respect for their craft. I don’t know how they do it, but I understand how complicated it is to perform in front of all the crew and the equipment and putting yourself in such a dramatic moment. To find the concentration sometimes is really a challenge, so I try always to do my best to make sure the cameras really serve the story and serve performers.

With Michael, nothing is pedestrian. Sometimes when I do shots and the timing is just perfect, he doesn’t like that. Often he loves to use the first take because there is a messiness to them, and he loves that mess. He loves the fact that the camera doesn’t know exactly where to go and has to find its way. It’s a process of his that I now understand after so many years. Sometimes I do a great shot, and I say to myself, “Whoa! This is such a great take!” And he goes, “That’s not at all what I want.” I love that fact because there are so many cliches in the movie business. Like, a lot of people say when an actor moves, the camera moves. They stop, the camera stops. But it’s not true at all. Because sometimes he stops and the camera moves because you want to tell something that’s happening in his brain, or you want to discover something behind them. There are no rules in the movie business, and Michael surprises me every time, because even though I know him so well, sometimes I go, “Oh, that’s a good take.” And he goes, “Let’s go again.”

Camera Operator Winter 2024

Above Photo: Roberto De Angelis, SOC, filming FERRARI

Photos by Lorenzo Sisti, Eros Hoagland, and Adam Driver

TECH ON SET

Sony VENICE 2 Camera

Panavision Panaspeeds, Panavision Primo Zooms, Angeniux Zooms, and Fuji Premiere Zooms

P+S Technik Skater Scope

Scorpio Arm Car

Correction: A previous version of this article listed Panavision Primo, Super Speed, and H Series lenses in the “Tech on Set” section

RELATED CONTENT

Roberto De Angelis, SOC

Learn more about Roberto’s career and projects at IMDB.com

Camera Operator

“Snake Eyes: GI Joe Origins: Action in Multiple Styles,” Summer 2021

BEHIND THE SCENES

Select Photo for Slideshow

Roberto De Angelis, SOC

Roberto De Angelis is a camera and Steadicam operator born in Rome, Italy. De Angelis’ feature credits include several projects with director Michael Mann, including the feature films Ferrari, Public Enemies, and Blackhat in addition to the episodic projects Luck and Tokyo Vice. De Angelis’ other credits as camera operator include James Cameron’s Avatar, Jon Favreau’s The Jungle Book, Michael Bay’s 13 Hours and 6 Underground, Edgar Wright’s Baby Driver, Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, and Olivier Dahan’s La Vie en Rose.

A writer and critic for more than a decade, David Daut specializes in analysis of genre cinema and immersive media. In addition to his work for Camera Operator and other publications, David is also the co-creator of Hollow Medium, a “recovered audio” ghost story podcast. David studied at the USC School of Cinematic Arts and works as a freelance writer based out of Long Beach, California.