Shooting Myself: Careening Toward Enlightenment in the Entertainment Industry

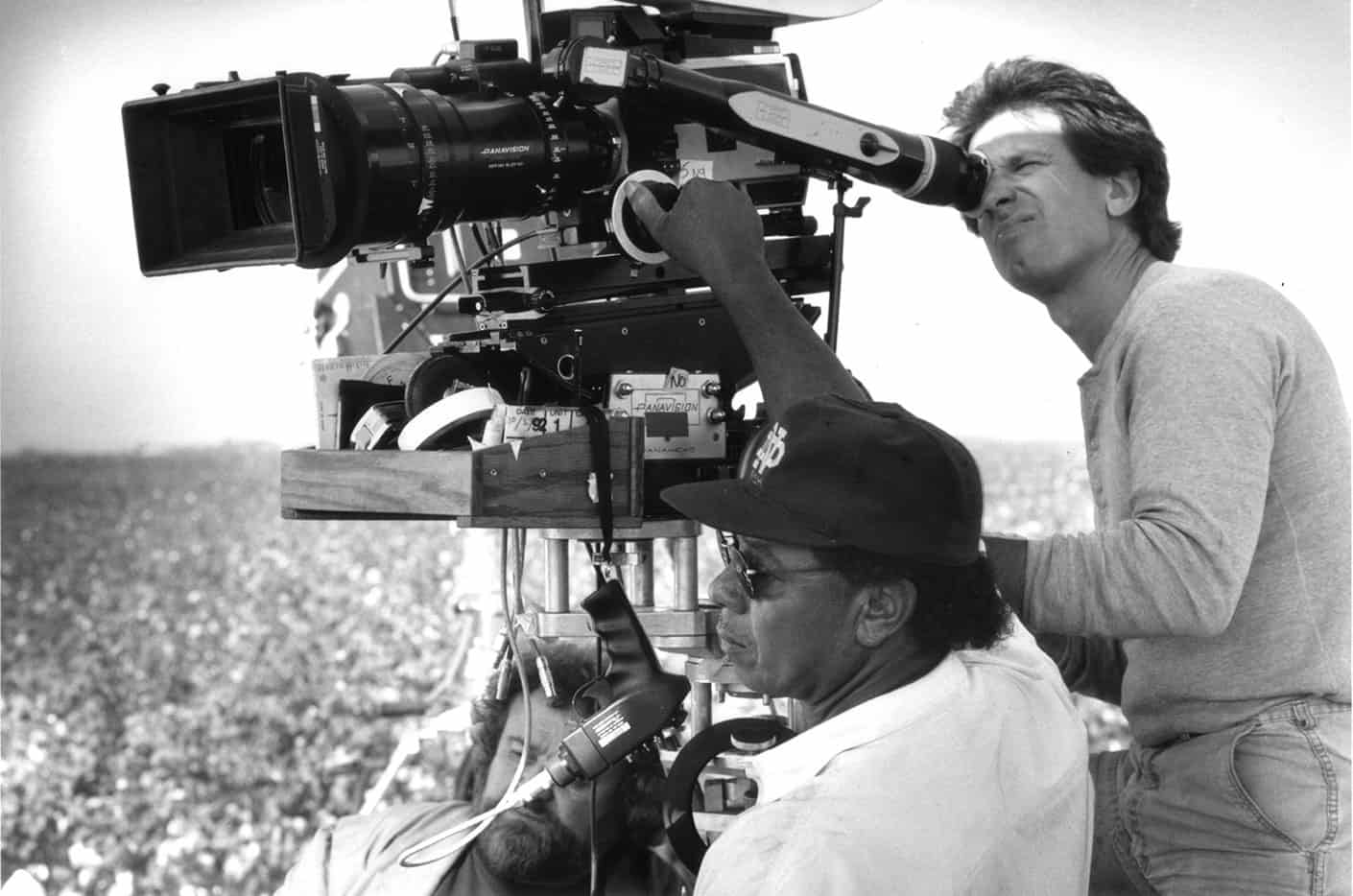

Above photo: Director of Photography, Allen Daviau, 1st Assistant Camera, Reggie Newkirk, and Camera Operator, Paul Babin on location near Bakersfield, California for the airliner crash aftermath in Fearless. Photo Credit: Merrick Morton

By Paul Babin, SOC

In 1992, I was hired to be the camera operator on movie that would change my life, and would forever shift how I looked at the unique, collaborative, creation process we call filmmaking. I would compare every director and production experience to the standard that film set. After it, I found myself passing on what I’d learned to anyone who would listen.

But before I go into that, a little back story…

I GET A preview of MY CAREER (IN LESS THAN 24 HOURS)

I was like a deer in the headlights after I left USC film school and began knocking on doors in Hollywood. My goal—to become a director of photography. My desire—to be seen. My self-esteem—paper thin.

Early in the process, I encountered one of my heroes on the street. John Alonzo was a director of photography best known for photographing the movie Chinatown. Meeting him was a real thrill. I told him how much his work inspired me. I described how I had succeeded in getting into NABET, but at the same time I was frustrated by my inability to get into IATSE local 659, the camera union having jurisdiction over features.

Alonzo was a handsome, magnetic, masculine guy. He listened patiently, looked me right in the eye, acknowledged me to my core, and with genuine sincerity said, “Paul, here’s what you’re going to do; you’re going to make an appointment to see Dick Barlow at Warner Bros., he hires camera assistants there. And you’re going to tell him I sent you.”

This was a profound moment of being seen. I floated home on a cloud of rapture and called Dick Barlow, “Mr. Barlow, John Alonzo suggested I call you. He said I should come in and introduce myself?” A gravelly voice on the other end of the line said, “I get to work at 6:00 AM.” And before I knew it, the call was over.

Forty years ago, there were no metal detectors at the studio gates. There were barely gates. If you walked with authority and an attitude of ‘I’m supposed to be here,’ it was possible to walk right onto a studio lot unchallenged. And that’s what I did the following morning at 5:50 AM.

I entered the office of Dick Barlow at 6:00 AM. The receptionist hadn’t arrived yet. Down the hall through an open doorway I could see feet propped up on a desk. I meekly walked toward them and into the office Dick Barlow.

Mr. Barlow was reading a newspaper. For an instant, his attention shifted away from the newspaper as I introduced myself and sat down in a chair opposite his desk. I launched into describing my desires and limited experience. Mr. Barlow continued to read the newspaper—the sports section. I vividly remember that it was the sports section because he never put the newspaper down. With only a page of box scores to look at, I delivered my soliloquy and ran out of steam after about five minutes. Two minutes of really uncomfortable silence followed after which I stood, thanked him for his time, and left.

Dick Barlow was not interested in seeing me.

This encounter with two veterans of the industry set a pattern I would experience throughout my career. Of course people who related to me like Alonzo would encourage and inspire me to new heights. Those who put up a wall and shut me out like Barlow would not; in fact, as I grew in confidence and experience, my resentment would occasionally prompt me to “set fire to the sports section” just to make a point.

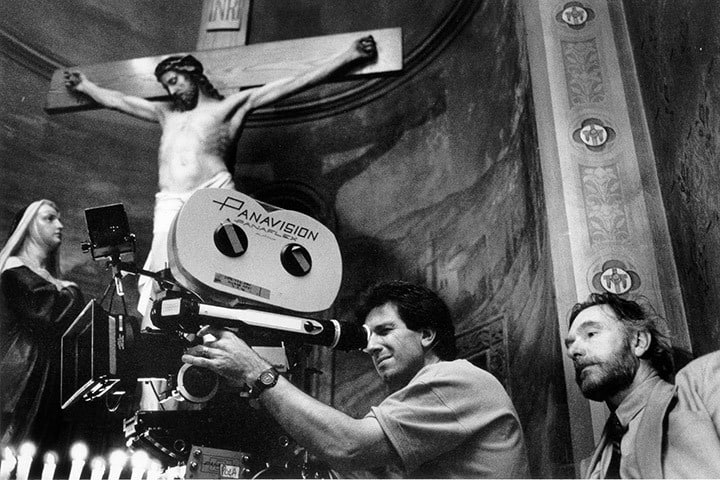

Babin and Director, Peter Weir in Saint Peter and Paul Church, San Francisco, California. Photo Credit: Merrick Morton

The Desire

And what was the point?

Well, have you noticed that all of us, regardless of whether we’re an extra hammer or an executive producer, share a common experience? It goes like this; we work on a project and devote our time, attention, blood, sweat, and tears to it. Then we go to the cast and crew screening, or sit in our neighborhood theater, and our work comes up on the screen and we have this emotional experience of: I did that! It’s like, if we could, we’d stand in front of the screen, point to ourselves, and announce, “I did that!”

All artists have this. Every human being, at some level, has it:

The desire to be seen

The desire to be seen is a basic human need. And here’s the point; when this need is met we come alive. We are creative and available on a whole new level.

“I’m here to be seen, I see you”

In the Zulu culture of South Africa, this basic need and the power of acknowledging it is built into the words people exchange when they meet. Two guys run into each other on the street it’s not,”Hey, dude, wassup?” “Oh, nuthin’.”

Rather, it goes like this; the first person says, “sikhona”, which means “I’m here to be seen.” The second person responds with, “sawubona,’ which means “I see you.” Then it reverses as the second says, “I am here to be seen,” and the first says, “I see you.”

Try this with someone. Make eye contact. Resist the urge say anything other than, “I’m here to be seen. I see you.” Speak slowly. Notice how these eight words cut through pretense and call on the “real me” to show himself to the “real you,” and recognize that we are both more than our screen credits, job title, the car we drive, or who we’re dating.

EXPECT THE UNEXPECTED

The production experience that so rocked my world in 1992 was Fearless, starring Jeff Bridges and Rosie Perez. Fearless was directed by Peter Weir, an Australian filmmaker whose work at that point included; Witness and Dead Poets Society, both powerful movies.

I knew Peter was a great storyteller. What I didn’t realize as I arrived in San Francisco to begin filming, was that I was about to experience a style of leadership that encouraged both cast and crew to be vulnerable, to see one another as equals, to bring out the best in each other, and to participate fully in the making of the film.

Though he never said the words, “I’m here to be seen. I see you,” Peter Weir showed up every day with that attitude. In the way he said, “Good morning,” and paused to connect, and in the way he listened without an agenda. One day, honest-to-God truth, I went to get a cup of coffee. Peter was discussing the film with the craft service guy, listening to his ideas with the same focus he gave to his cast.

Jeff Bridges put it simply, “Peter valued everyone. (It was) was empowering.”

Peter had an expression he uttered many times and always with a twinkle in his eye, “Expect the Unexpected!” In a 2010 interview he said, “I like positive energy on the set—mixed with a kind of recklessness, a bit of danger. The danger being—we might change things altogether. We might do something unexpected. We might make up a new scene. Or we might shoot the whole thing in one shot. We’re not locked. The day has a reality to it.”

What so profoundly affected me on Fearless, and has became clearer over time is this, Peter Weir understood that the most valuable resource he had was the people around him. He understood that a crew can impact the creative process in a way that goes far beyond setting C-stands and choosing lenses. He understood the importance of nurturing the collective energy, or vibe, or the mood of his cast and crew. “I’m here to be seen, I see you,” or Peter’s version of it is what accomplished this.

Another way Peter shaped the collective energy was through music. “For me, music is probably the most primary tool I use in script, shoot and cut. I play it against dailies. I play it against cuts where I turn the sound down. I make up CD’s for use on the set.”

In 1992, is was a cassette tape in a boom box with a playlist of about ten pieces of instrumental music that ranged from Heinrich Gorecki’s Symphony No. 3 to a Phillip Glass/Ravi Shankar collaboration. (Note to readers under 30: A “boom box” was like an iPhone except you couldn’t text with it, and there was no search engine. The only app in it was the sound it made when the cassette tape broke and it spun freely: app, app, app). Peter would play one of the selections during rehearsal. He’d switch it off while the crew set up the shot, or leave and return with his boom box a few minutes before the cast arrived and start the music again. The actors would rehearse to music. We’d roll. Peter would typically be next to camera. He’d say, “And…fade out the music—action.” The sensation I experienced in that moment, as I pushed my eye up against the chamois and cradled the wheels, can only be described as one of connection, of being divinely in sync—with the actors, the scene, my assistant and dolly grip—with a source of creativity that roared through the sacred space around camera.

Just for the record, I had seven years of sobriety at this point.

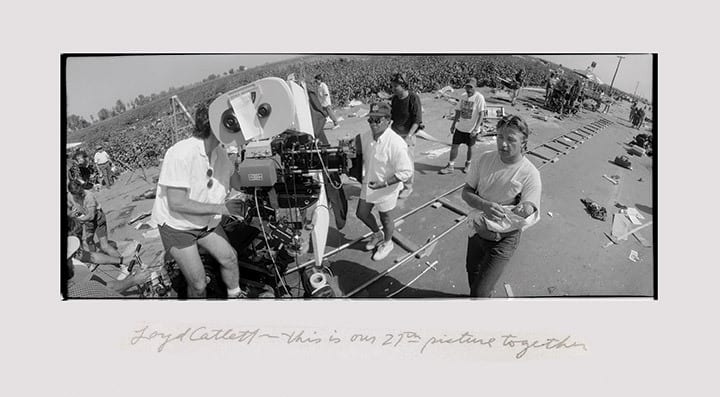

Photos from the set of Fearless by Jeff Bridges. © (1992) Jeff Bridges All Rights Reserved

WHEN THE LOVE-IN GOES SOUTH

Toward the end of production on Fearless, Jeff and Peter’s relationship was tested.

Jeff described it recently, “We were filming the plane crash. It was one of those 14 hour days, and for one reason or another we filmed all of the passengers in the plane before we got to me.

(All) that day I had felt tons of adrenaline going through my system. When they finally got to my close-up, I was wiped out. I had shot my wad. And I remember Peter is down on the floor with all you guys, and he was exhausted. Everybody was exhausted, and I’m acting, ‘Ah, fu*k, were going down…!’

And after the first take (of my close-up), Peter says, ‘Don’t open your mouth like that, because the light is going in there and it’s not good, you know.’

So then I said, ‘Well, I can go like this,’ and I made a face like I’m blowing a kiss. ‘Or I can go like this…!’ and I made a face like I was smiling. I was being petulant, way over the top.

After doing that for a minute or so, Peter looked at me and said (with a sense of resignation and disappointment), ‘Yeah, do it like that.’

And I said to myself, ‘Ah shit, what have I done to my director?’ I just felt terrible because we got along so well, and I felt like I had sabotaged the day’s work.

The next day before work, Peter came to my trailer and he said, ‘What was that all about?’ And I found myself getting very deep, talking about the material we use as actors to do our work. I got very emotional. I was crying and weeping. Feeling like I’d disrespected my director who I loved so much.

Then, Peter expressed all of his vulnerabilities and concerns, and how much he counted on me, and how when I did that, it hurt him. For about half an hour we really got down to it. We had the chance to express our fears and pain, and what that was all about.

When I went to the set, I got the attention of the cast and crew, and I apologized for being disrespectful to my director. I said, ‘I love our movie. Let’s take it to the next level.”

That’s what can happen when you address some of this fear and pain that we all go through. When you can share that you can reveal whole new levels of communication and creativity. You got to let the shit rip.” (The Dude’s way of saying, “I’m here to be seen, I see you.”)

Photos from the set of Fearless by Jeff Bridges. © (1992) Jeff Bridges All Rights Reserved

BEING SEEN AND SEEING—FEARLESSLY

I’m not suggesting that you go out and do the “I’m here to be seen. I see you.” on the next job. Unless you want to blow some minds. But you can bring that attitude to the set.

If you’re on the crew you’ll be a better contributor and collaborator. You’ll have more fun. People will hire you because they’ll like being around you.

If you’re a department head, director, or producer, it will make you a stronger leader. You’ll find it a powerful, creative tool in the production of your film.

One caveat—another word for the concept of “I’m here to be seen” is “vulnerable,” so if you try this, it will call on you to be fearless.

Jeff Bridges gets the last word on this one, “The truth is, we are all very vulnerable and we are all very sensitive. And that’s a gift. That’s a wonderful thing. Fear may drive you to your knees; it may break you right down, but that’s not a bad thing. It’s what you do with it.”

Paul Babin, SOC

Paul Babin, SOC

This is excerpted from Paul’s forthcoming book: Shooting Myself: Careening Toward Enlightenment in the Entertainment Industry. Paul Babin, SOC, is a camera operator, a life coach, and an adjunct professor at USC School of Cinematic Arts. He was recipient of the 2012 Lifetime Achievement Award from the Society of Camera Operators. He is a painter, sculptor and singer-songwriter. Photo Credit: Paul Babin

Read More Stories from Camera Operator

Print and Digital Versions Available