Being the Ricardos: An Exercise in Trust

An interview with Peter Rosenfeld, SOC, and Lukasz Bielan

By David Daut

During the height of Cold War paranoia, the American public heard a startling accusation: actress Lucille Ball is a member of the Communist Party. Being the Ricardos is Aaron Sorkin’s third feature as writer and director, and the film stars Nicole Kidman as Lucille Ball and Javier Bardem as Desi Arnaz.

As much as Being the Ricardos is a film about the lives and relationship of Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, it’s also an exploration of the creative process, zooming in on a particularly turbulent time in the production of I Love Lucy amid allegations of infidelity and “un-American activities.”

Being the Ricardos follows a week in the making of an episode of I Love Lucy—from table read to filming in front of a live studio audience—as Lucille Ball, Desi Arnaz, and the creative team behind the show attempt to keep production on track while fallout from these rumors threatens both the show and the personal lives of those involved.

In talking with camera operators Peter Rosenfeld, SOC, and Lukasz Bielan, they expressed some kinship with the characters they helped to recreate. What resulted was an extremely close working relationship between camera operators and a level of individual creative freedom seldom seen in the industry.

While writer and director Aaron Sorkin focused on dialogue and performances, he deferred much of the task of crafting the film’s visual language to director of photography Jeff Croenweth as well as Rosenfeld and Bielan. It was a totally unique way of working for them, a fact that’s reflected in the credits of the film.

In their conversation with Camera Operator, Rosenfeld and Bielan talk about their working relationship over the years, the unique way Aaron Sorkin directs, and the importance of building trust in the relationship between actors and operators.

Nicole Kidman on the set of BEING THE RICARDOS

Camera Operator: Before we started, Peter, you were telling me that you just got the opportunity to see the movie last night? I guess first off, what did you think?

Peter Rosenfeld: My thought was that the cinematography really supports the story and it doesn’t in any way overpower or overshadow it or become so blatantly noticeable that it distracts the audience from what is really a wonderful narrative. I think we did the movie real justice. The shots are concise, they’re smart, they’re beautifully lit, and they support the dialog at every juncture. What do you think, Lukasz? Do you agree?

Lukasz Bielan: When we did it, we already thought about that. Enhancing it by helping him tell the story. Jeff [Cronenweth] gave us so much freedom. It’s such a great experience on every level, just working with somebody like Peter, who is much, much, much older than I am [laughs], which is a side note.

Rosenfeld: [Laughs] Actually, you’re mistaken. Lukasz looks younger, but he’s much, much, much older than me. In fact, he was an operator when I was still in grade school.

Bielan: [Laughs] I can’t wait to see it. I’ve seen snippets of it and the trailer and everything else, but I just know what wonderful things Aaron [Sorkin] said about the movie and how proud he was of it and how happy he was that he had us, which is extraordinary for a director to mention that in a public venue.

Rosenfeld: It’s never happened to me. I’ve never had the operating singled out like that before. We don’t live for that, though. We toil in the shadows, Lukasz and I. We toil in the shadow of great artists.

Bielan: Yes, exactly.

CO: You talked a little bit about working with Jeff Cronenweth and Aaron Sorkin. Could you talk a little bit more about what that working relationship was like?

Rosenfeld: I have a memory that may be indicative of what it’s like to work with Aaron Sorkin as a director. We were figuring out a shot, Lukasz and I, about how to get an actor from one side of the corridor, down the corridor, and into a room. The dialogue was too short and couldn’t carry them far enough. I think it was Nina [Arianda] and Nicole, if I remember correctly. We were kind of huddling, trying to figure this out and Aaron walks over and goes, “What’s up, guys? What’s the problem?” I was a little bit embarrassed to say that we were hoping to start them there and bring Nicole over to here, but we ran out of dialogue. He looks at me and says, “You ran out of words?” And—I kid you not—he drops to the floor in front of us. Drops to the carpet, opens up his laptop, and starts clicking. He looks up at me and goes, “How long? How much time do you need?” I say maybe about ten seconds. “Okay, no problem.” He’s writing, Lukasz and I are looking at each other, and then he stands up with his computer, goes over to Nicole, they review the new dialogue, they run it in the first take and it was perfect. That’s what it’s like to work with Aaron Sorkin. Afterwards he comes up to me and he says, “Never be afraid to ask for more words.”

Bielan: Aaron is a writer, first and foremost, then a director. I think one of the reasons—and Jeff will agree with this, he’s the one who has actually told us—he needed somebody with a strong visual eye to up his game as a filmmaker. That’s why he chose Jeff. He’s worked with him before in the capacity of a writer, but not as a director. Jeff’s vision is extraordinary in every way because it’s simplistic, but it’s perfect for the period of this movie. With his lighting, he allows the actors to do whatever they want. He lights the environment, they fall when they’re supposed to fall in, and then he enhances the close-ups the way they should be. Because of that, he also gave us a lot of creative freedom to come up with compositions.

Working with Pete in that way was one of the best experiences ever because we just fed off of each other. There’s no ego involved, we both are secure in what we do. And the thing is that we truly love each other. We’re very good friends, all three of us, and I think that the trust we have in each other has a big impact on the creative process.

Javier Bardem, Christopher Denham, Nina Arianda, J.K. Simmons, and Nicole Kidman in BEING THE RICARDOS

Rosenfeld: Totally. I want to pick up on that too. I never really thought of it that way, but you, me, Jeff, we have relationships that go back 30 years, so the amount of trust that we all have in each other was certainly evident on set. Lukasz and I, from the first day, we started immediately thinking about the way we record the action, where we place the cameras, how we can cover something efficiently, but elegantly. We didn’t have a big budget, we didn’t have a lot of days, so we had to be very efficient in terms of how we were setting up the shots.

We did a lot of shots where I would take someone from A to B, Lukasz would pick them up from B to C, developing shots so we wouldn’t have to interrupt the performance. I had never worked so closely in blocking out the coverage with another operator. The process on set was just as Lukasz described. Jeff would say, “Okay, I’m lighting for here with these big windows and pushing through here, she’s gonna look great around this area.” Then we would watch the director do his blocking rehearsal and Lukasz and I would huddle in the corner like a couple of conspirators, whispering to each other. We would figure out the coverage on the fly. Both of us have a fair amount of experience, so we can understand how to optimize the blocking. It became very evident that this was going to be our process on the movie.

Bielan: It just became our language and it was so organic. Nothing we came up with was convoluted, it was just things that we both saw, as Peter mentioned, based on our experience, but we also wanted to be original in what we’re doing because this movie is so original. For instance, when you’re shooting the cast from the back looking out at the audience, we have so many angles to cover in a short amount of time, and make it interesting, while keeping it consistent with the story. We’ve got to figure it out with Harold [Skinner], our gaffer, who came in for the third camera. We helped him with the framing and where to put the camera, because obviously he’s not an operator, but he did an amazing job. Again, it was organic and subtle and told the story the way it should have been told, in my opinion.

Rosenfeld: Let me pick up on the C camera and Harold, because of the way Sorkin writes, a lot of people are talking. While the leads are talking, someone else is having a side discussion between two other people, and that dialogue is interwoven and overlaps with the principles. Because of that, often we would not only have two angles on the principles, observing correct screen direction, but now you have another conversation going on with its own inherent screen direction. So, Lukas and I would often put Harold—or “H” as we called him on set—we would put H on one of those shots, so we can start knocking off all those little sub-conversations that are going on at the same time. This happened quite frequently.

Bielan: Aaron is one of the first directors I’ve met who would actually insist that the actors overlap. For a sound guy, it’s a nightmare, but he says, “I want overlaps. Just interrupt, go over each other’s lines.” That’s how he works, that’s how he writes, that’s his aesthetic, so we have to transcribe that into visuals, hence the third camera coming in and figuring out the angles.

Rosenfeld: About a week or two into this movie, I did something I’ve never done. I pulled Jeff aside, and then I pulled the producer, Stuart Bessor, aside and I said, “I want to change my screen credit. I don’t want to be listed as an A camera operator, because the way we’re working on this show, we’re working completely as co-operators, we’re completely working together in tandem, and I just want to be credited with Lukasz on one line as camera operator. Do you guys have any problem with that?” They didn’t, and thank God they didn’t forget and we’re credited that way on the movie. That to me is a testament to how we shot the picture and worked together as camera operators.

I would completely trust him. If he had the developing shot, I wouldn’t be put aside at all. I would just be thinking, “Okay, so that’s the shot now. What can I do in here? Can I pick out any piece that’s missing?” And he would do the reverse. There was no ego, there was no one-upmanship; it was one of those synchronous on-set relationships, one being the extension of the other. Normally, you know, movies have a certain protocol. There’s usually a main shot that everyone throws their energy on for lighting, visual effects, whatnot, and then the B camera’s often sniping within that or trying to pick something off. That wasn’t the way we worked on this movie. We tried to make each shot count, to make everything interlock with the previous shot and the one that followed. It was a methodology I’ve never experienced before, and the credits reflect that.

Alia Shawkat, Nicole Kidman, and Nina Arianda in BEING THE RICARDOS

Bielan: I am humbled. I’ve known Peter for a long time—our first movie together was Down with Love with Jeff as a DP—and I’ve always looked up to Pete and what he does. You know, you follow friends on IMDb to see what they’re doing, see what’s happening, and you wish you could work together, but we both moved on. I’ve been a B camera operator for a while as well, and I moved on many years ago to do A camera, but when this opportunity came, it was unbelievable.

Rosenfeld: Picking up on that, you have to realize that, as both of us are A camera operators, we rarely get to work with other A camera operators. They’re busy on their movies, there’s only budget for one A, whatever the reason. Lukasz’s involvement in this picture changed the dynamics for everybody and made the movie so much better. There’s also his personality, he’s very loving on set, he’s very kind and people love him.

Part of what an operator has to do is win the trust of the performers, not just the director and the DP. The actors have to look at us in that moment of insecurity that every single actor has sometimes, that moment where they look up, and the first person they see is Lukasz. And he’s smiling back and he’s blowing them a kiss or saying, “It was beautiful.” That means so much.

Bielan: Same goes for Peter over here. You know, actors also trust us as the last bastion between reality and the screen. So many times they will look up to you as the operator for confirmation of what they just did instead of going and waiting for the director. In a way, we’re sort of like psychologists—

Rosenfeld: [Laughs] We’re therapists. We’re on-set, shot therapists.

Bielan: And if you don’t have the trust of an actor, it could be miserable. If you have that trust like we had with Nicole and Javier, it takes it to a different level. On this movie, Aaron is a person who cares a lot about the text—obviously because he’s a writer—so if he’s happy with the words he’ll move on. We have a cast who are searching for their characters, but because they’re portraying somebody else, one or two takes is not enough. Many times the director would say, “Okay, moving on,” but Nicole would wink at Peter or Javier would wink at me and we would know that they need another take, but can’t ask for it because of the unwritten protocols. So we’d say, “Aaron, we had a little camera thing. Can we do one more?”

Rosenfeld: I actually forgot about that. I’m glad you mentioned it, because that was an important part of building trust with the performers. Aaron would say, “Great! Moving on!”

Bielan: And you would see that Nicole or Javier were not ready. They didn’t find what they were looking for.

Rosenfeld: And if they asked him for another take, Aaron would often say, “Why? Nicole, that was perfect!” So they learned that if you go through Lukasz, or you go through myself, and we ask for another take, Aaron wouldn’t fully understand, but he’d say, “Okay, no problem. Lukasz wants another one.” Boom, we do another take. Not for us, but we’re doing it for them. We did that with some degree of regularity. When either one of our principals felt like they need another take to refine something, they would generally go through us.

Javier Bardem and Nicole Kidman in BEING THE RICARDOS

Bielan: My story of Aaron is when he’s directing from the monitor, sometimes he goes away and just listens. He doesn’t even look at the screen or what’s happening. He just listens to the words and says, “Okay, cut. We got it.”

Rosenfeld: I busted him on that once, actually. Lukasz was running a single camera set up by himself and I went over to the monitors to watch and Aaron was doing exactly that. He had his head down looking at his computer and he wasn’t watching. Then he said, “Cut! Great!” And I said, “Aaron, you weren’t looking!” Aaron says to me, “but I trust you guys. If there was something wrong, you’d tell me.” I said, “For sure we would tell you, but maybe there’s a subtlety that we may not see.” But anyway, he is really an amazing writer, and he wants to protect his work, and he mostly left the fabrication of the imagery to Jeff, Lukasz, and myself and Jon Hutman, our production designer.

Bielan: I think the word is complete trust. Going back to what we said in the beginning, he looked for somebody like Jeff, who would elevate his words with the visual aspect of it. And by meeting us, and by being together, we gained his trust, and he was able to not look at the monitor because he knew he would get it.

CO: Speaking to the dynamic way you made the movie and sort of figuring things out on set, as much as this is a story about Lucille Ball and her personal life, it’s also very much an exploration of the creative process. Being up against the timeline of shooting a TV show, plus all the stuff that’s going on in their lives outside of that, and trying to put all that aside and just focus on the work. Make it as good as possible and come up with those sort of moments of inspiration on the fly. Did the way you worked on this lend you a sense of connection with the characters?

Bielan: The funny thing is, it’s one of the few movies you work on where after eight hours you’re done. Our days were relatively short, because if he’s happy with the words, he’s happy with where it’s going.

Rosenfeld: The story that’s told in the movie is somewhat mirrored in the story of the making of the movie where it’s a very short schedule, where there’s a lot of pressure to make the coverage in the hours allotted—we know we’re not going to do any 10 hour, 11 hour days—and we have a director who’s keen to move on. The pressures that were inherent in the daily staging of the blocking and the lighting and the shooting were similar, sometimes, to the to the stresses that Lucy and Desi were going through in our story.

CO: One of the more interesting stylistic choices that the movie makes is that we get to occasionally be inside Lucille Ball’s head as she’s working through that creative process and having these moments of inspiration and these moments play out in black–and–white in the style of the I Love Lucy TV show. What went into recreating the look of those moments while at the same time adapting it for a widescreen frame and modern technology?

Rosenfeld: The first thing that comes to mind that’s probably going to be of interest to our readership is the unconventional framing for these sections. I say unconventional, but really what I should say is 1950s-style framing where you would have a three-shot with that square frame, lots of headroom, and no coverage. Those scenes had to be shot that way because that was the style in which they shot the original show. So we were somewhat limited in what we could do, we had to embrace those kinds of compositions.

Then, of course, there was the stylistic choice to render those shots in black-and-white, which I thought worked quite well. I was always wondering about that transition, but it works really, really well. You always preceded it with a close-up of Nicole thinking, and then she sees the scene in her head as it will be shot. The black-and-white and the composition and the use of the cameras—you know, the cameras never moved—that was dictated by the material. In other words, we had to embrace that kind of framing.

Bielan: Exactly what you just said, it’s the way that the show was shot. Desi Arnaz gets the credit because he developed the three-camera system that did not block the live audience watching the show. Before that, when they filmed things, everything was blocked so people could not see, but he organized the cameras in a way that they would be far enough back and situated so that they could shoot the material that they need, but the audience would still see what they wanted to see live. But beyond that, there’s also the four-by-three frame, which we’re not very big fans of, and the headroom and the composition. It was typical TV; that was the standard back then. But the thing I think is great is that we did not overload it with the black-and-white footage. Modern movies, when they have flashbacks, they have so much material that sometimes you just get tired of it, so I thought it was very smart of Aaron just to pick these few moments.

Nicole Kidman in BEING THE RICARDOS

Rosenfeld: You’re absolutely right, it wasn’t overused. I think maybe there are three or four times where he does that, but it’s not something that becomes like “oh, here we go again into the flashback.” It’s almost like giving the audience a little bit of a treat, like “oh, here’s what the show looks like,” and then she comes out of it and we’re back in the writers’ room. It was put in almost like a little bit of a tease more than anything else.

Bielan: We also had a monitor on set just before each take for each scene that we filmed with playback of the real footage. So we looked at it, we looked specifically where the headroom was, what the composition was, and how we could adapt it to our production design and make it suitable for the movie.

Rosenfeld: I remember also that Nicole would study it. She would be there, inches from the monitor, just studying Lucille Ball. You could see her mouth moving and she was memorizing the actions. I’m thinking in particular of the scene where she steps in the grapes and Lucy has that great, exaggerated expression. She studied that moment, I was there when she was doing the playback, and, of course, she nailed it when our cameras were rolling. With that on-set monitor playing back the original show, she was able to fine-tune her performance and Lukasz and I fine-tuned our period framing.

CO: That’s really interesting. Like you said, there’s not too much of it, but just enough to kind of give that little bit of familiarity as well as a peek into her mindset in these moments.

Bielan: Yeah, because the movie is not about the I Love Lucy show itself. It’s about Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz and their relationship and how she takes those ideas and develops them.

Rosenfeld: It’s a week in the life. It’s a very stressful week in the life of these two television personalities. It’s an actors’ piece. It’s not a comedy; it’s a drama, as far as I’m concerned. There’s comedy in it, but I think that was a misconception in people’s perception of what this movie would be.

I wanted to talk about the first time in the movie where we see the faces of our leads. It’s the first five pages of dialogue in the movie and Aaron did not want to reveal the face of Nicole and Javier until the fourth page of a five-page scene. The story’s told with them out of focus, our audience only watches the cabinet-style radio in the room, listening to the voice of radio commentator Walter Winchell. Occasionally you see little snippets of them or their actions in the cabinet mirror—which was a genius idea from Jeff Cronenweth—like the magazine hitting the floor. That was a real challenge for us. How do we do four pages of a scene, with ongoing dialogue, without ever revealing the characters’ faces? I think the concept—which was Aaron’s concept—really, really worked. The only time you see their faces is when Winchell says, “A leading television personality is accused of being a communist,” and cut, you’re now looking at them. And Nicole goes, “What?!” And Javier goes, “What?!” And that’s the first time in the movie we see them. I thought that was really clever. We can’t really take too much credit for that because that all that came up in prep before our involvement, but we certainly had to help reverse engineer all those shots in a way that would keep the audience interested. It needed to feel organic, but at the same time we could not reveal them. That was kind of a challenging piece of business that found its way into the script very early on.

Nicole Kidman and Javier Bardem star in BEING THE RICARDOS

Camera Operator Winter 2022

Above Photo: Nicole Kidman and Javier Bardem in BEING THE RICARDOS

Photos by Glen Wilson / Amazon Content Services LLC

TECH ON SET

RED Ranger Monstro shooting at 8K composing for 2.40 and a 10% reduction to preserve reframing possibilities in post and VFX “handles.” Cameras were fitted with LPL mounts.

Black-and-white portions of the film were shot with two RED Monochrome Helium S35 8K Rangers and one Monochrome Helium S35 8K DSMC2, all fitted with LPL mounts.

One full carefully selected set and an additional limited set of four ARRI DNA large-format Spherical prime lenses. No zooms.

A Talon remote head and Steadicam added flexibility to camera movement.

INSIDE SCOOP

Aaron Sorkin originally wrote Being the Ricardos with the intention of having someone else direct, but after enjoying his experience on The Trial of the Chicago 7, he decided to take on the job himself.

Lucie Arnaz—daughter of Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz—personally gave her blessing to Nicole Kidman taking on the role of portraying her mother. Later, she declared Kidman did a “spectacular job.”

RELATED CONTENT

Watch the trailer for Being the Ricardos

Peter Rosenfeld, SOC

Learn more about Peter’s career and projects at IMDB.com

Camera Operator Summer 2018: Ant-Man and the Wasp: Big Action, Small Heroes

Lukasz Bielan

Learn more about Lucasz’ career and projects at IMDB.com

Membership Content Portal:

SOC Lecture Series Class #7: The Role of the Operator: In Collaboration with the Actor

BEHIND THE SCENES

Select Photo for Slideshow

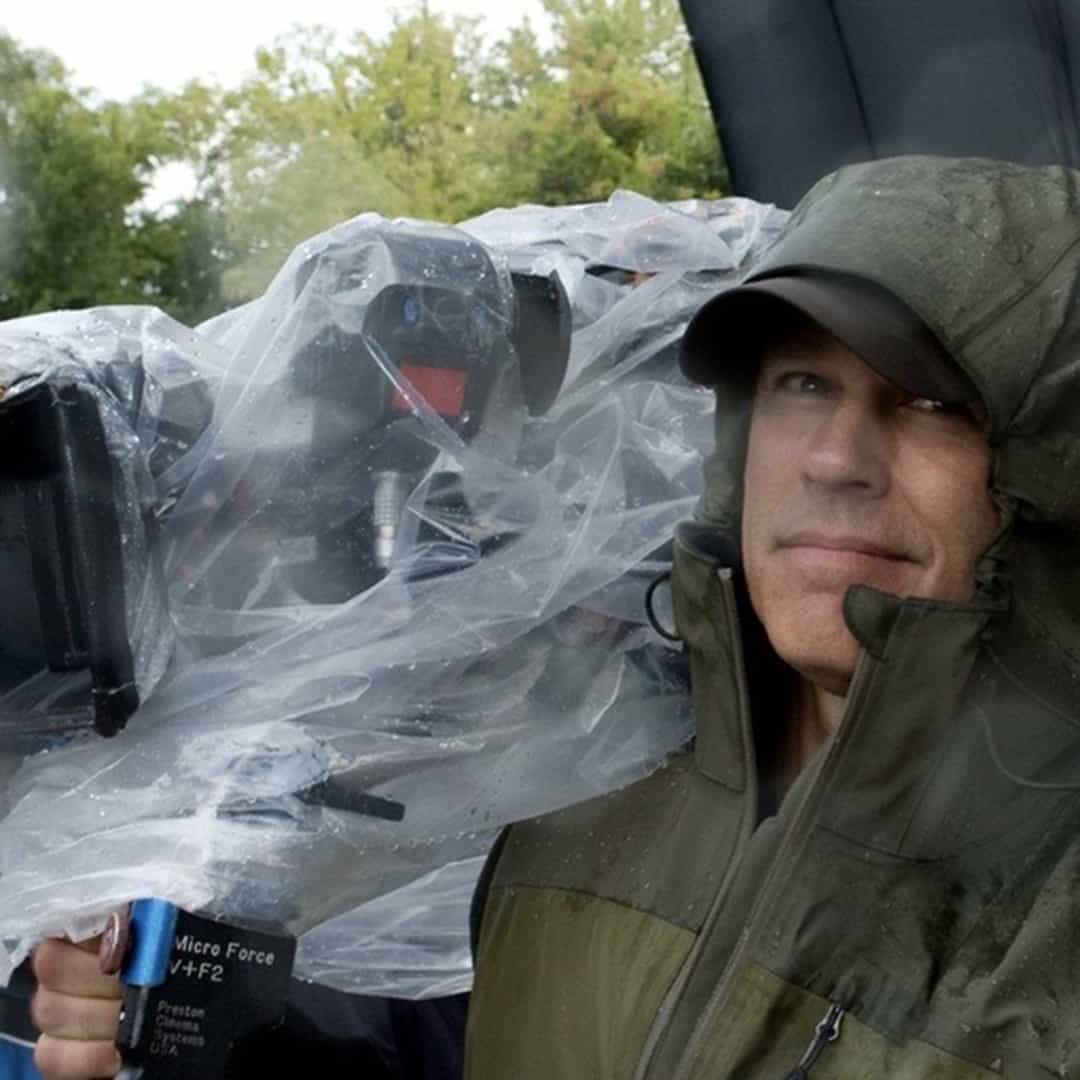

Peter Rosenfeld, SOC

Peter has been the camera operator on award-winning movies like The Social Network, Chicago, and American Sniper, as well as blockbusters like Spider-Man: No Way Home and Suicide Squad. Peter has operated for directors Oliver Stone, Rob Marshall, Kathryn Bigelow, Clint Eastwood, and David Fincher, among others. Early on, Peter acquired knowledge working as an editor that would serve him well as a camera operator. His well-rounded career includes extensive experience shooting news and documentaries, having worked for the BBC and CBC in foreign bureaus like China and Russia. Peter has covered many of the world’s hot spots and combat zones. He was assigned to Beijing during the Tianamen Square crackdown and found himself in Baghdad for the first Gulf War and in Germany where he filmed the collapse of the Berlin Wall. In addition to English, he speaks French, Mandarin, and Russian. He lives in Los Angeles with his wife and daughter.

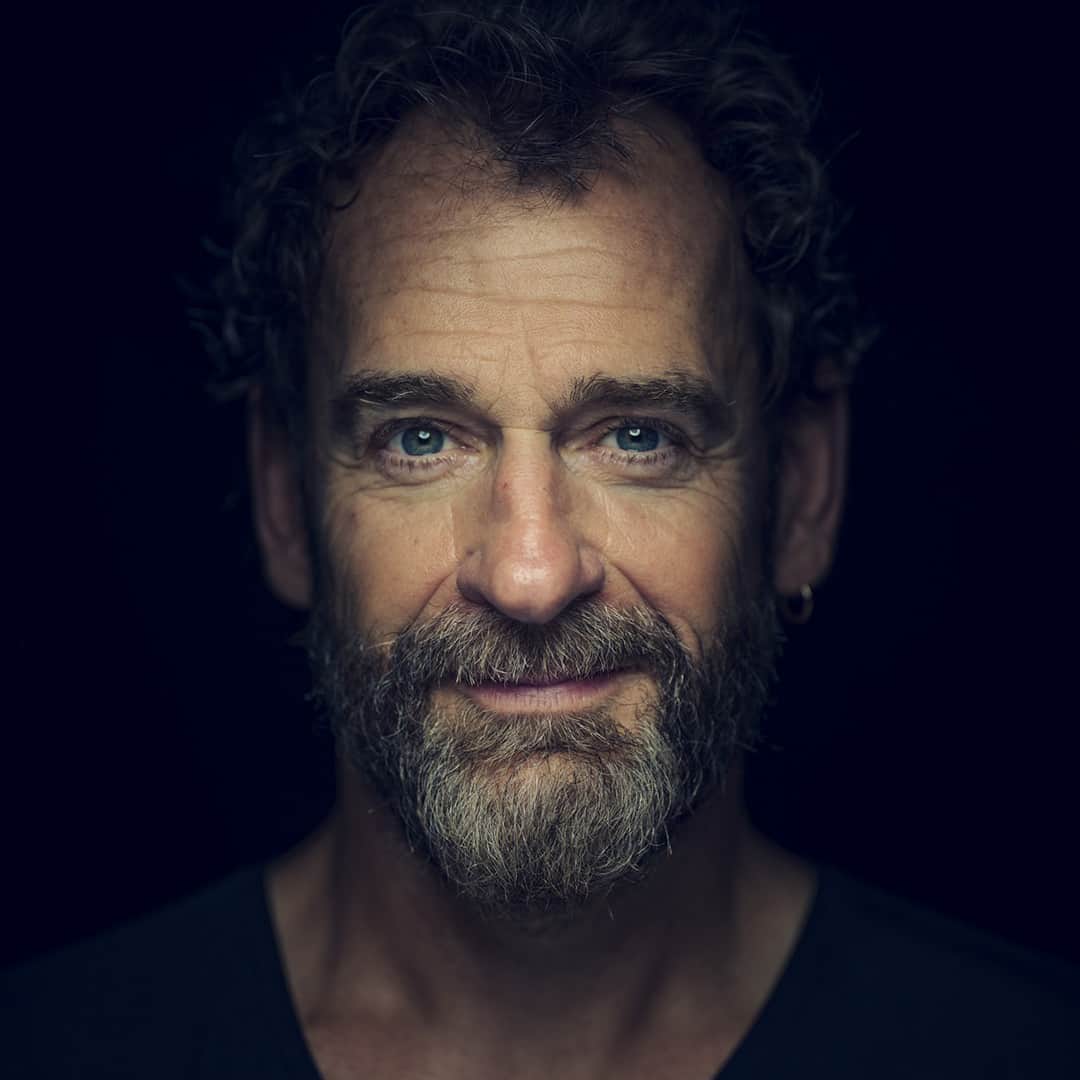

Lukasz Bielan, SOC

Lukasz Bielan was born in Warsaw, Poland. He started studying cinematography at Columbia College Hollywood. After a few years, he took a leave of absence to work with Sven Nykvist as his personal assistant and camera trainee on Chaplin. He stayed with Nykvist on the next nine films, including Sleepless in Seattle, What’s Eating Gilbert Grape, and Only You, climbing the camera department ladder from 2nd assistant to camera operator. His operating credits include Life of Pi, Deadpool 2, Public Enemies, Oblivion, Spectre, and Mosul. He has worked on most of the Transformers films and collaborated on many projects with Michael Bay, Peter Berg, and Michael Mann. He lives with his wife in Palm Springs, California.

David Daut

A writer and film critic for close to ten years, David Daut specializes in analysis of genre cinema and immersive media with bylines at Lewton Bus, No Proscenium, and Heroic Hollywood. David studied at the USC School of Cinematic Arts and currently works as a freelance writer based out of Orange County, California.

.